Chapter III

In Sunny Queensland

IF THERE were mixed emotions as the transports glided under the Golden Gate bridge and pushed their noses into the stormy seas ahead, there was a definite exhilaration that now we were on the way to do the job for which we had trained so hard. Mingled with these were thoughts of loved ones left behind and the realization that some of us, possibly many of us would never return. “Surely”, everyone thought, we will be back someday. The only question we ask is, “Which one of these slogans will be most accurate? Golden Shore in ‘44, back alive in ‘45, or (perish the thought) Golden Gate in ’48”. Most of us guessed between ‘45 and ‘48.

The next few weeks were long and monotonous. The transports moved, not in large convoys, but singly and in small numbers, zig-zagging their way by varied routes, through the Jap-infested waters of the Pacific, blacked out from dusk to dawn. Tours of guard duty and kitchen police aboard ship were almost welcome. Time was spent in playing cards (with or without money), reading every scrap of paper available (foremost of which was the ship’s daily paper), listening to the radio shows broadcast over the ship’s loudspeaker system, eating excellent chow, and sleeping. Most of the men got their sea legs within a few days, but there were some who were less fortunate. Everyone “sympathized” with these seasick buddies by bringing them delicious pork sandwiches, commenting on the roughness of the sea, and explaining how close land was - straight down.

There were two big events in the trip - the crossing of the Equator and of the International Date Line. For several days prior to their entrance into the southern hemisphere, omnious warnings were circulated about the coming visit of King Neptune and his Royal Court. When the day arrived, the Amphibs were surprised to see droves of men in various stages of dress and undress and painted like wild Indians cavorting about the ship. Instinctively they tried to make themselves scarce, but with so few hiding places available, they were easily ferreted out. They were given the pleasure of being presented to the “Royal Court,” the joy of having an odorous rotten egg and catsup shampoo, and the ecstacy of kissing the “Royal Baby.” Unforgetable! One of the fortunates (?) later remarked that he thought the whole thing was a frame-up, because he “never did see no line on the water that day.” The day they crossed the date line did not occasion any celebration. Some of the men lost a birthday anniversary (it was surprising how may were born on that particular day of the year), and it did seem strange to just skip a day on the calendar, but the men figured that they’d get it back some day. Most of them did.

Aboard the “SS Noordam” going overseas.

February 1943. 532 EBSR personnel participating in

King Neptune ceremony upon crossing the equator.

The scattered transports landed over a period of weeks at various ports in Australia from Sydney in the south to Townsville some twelve hundred miles up the east coast. Accumulating all their gear and moving it over the dinky, vari-guage Aussie railroad to the sites in northern Queensland, where the Amphibs were to establish camp, was a tremendous job in itself. Some were lucky enough to stop in New Zealand for a day or two enroute but, for most of the ships, it was a non-stop trip and no Japs interfered although one or two changed courses upon receiving reports of Jap subs.

General Heavey and his aide First Lieutenant (now Captain) Milton 0. Spelts of Lincoln, Nebraska preceded the brigade to Australia by flying from Frisco to Brisbane. Enroute they spent one night at little Canton Island in mid-Pacific. That night the Japs for the first time surfaced a sub a mile offshore and intermittently shelled the island for several hours. They thus became the first members of the brigade to come under enemy fire. Luckily no one on the island was hit.

In their grade-school geography the Amphibs had read about the terrain, cities, vegetation, animals and inhabitants of this faraway continent, and now they were anxious to gain additional firsthand information. They noticed that the Aussie vocabulary was full of new phrases and slang words like "Dinky doy,” “cobber,” and “fair dinkum.” Quickly adopting many of these new expressions, they in turn taught the Aussies many Yank idioms - both good and bad. At first the Amphibs experienced difficulty with the Aussie monetary terminology but soon learned the difference between a pound, shilling, form and penny. After a few weeks it did not sound at all strange to hear them saying “Shoot ya two bob” or “Betcha a quid.” They caught on. As they became better acquainted with their new surroundings, they noted a few other differences, but on the whole, the cities, farms, girls, beer, dancing and movies of Australia were so much like those in the U. S. that they could not help but feel very much at home with their new friends and allies.

The 532d EBSR landed at Townsville and, after a hectic railroad trip through flooded country, they encamped on the coast fifteen miles north of the town of Cairns, Queensland. Here their beaches were bordered by the beautiful but treacherous coral of the Great Barrier Reef. Brigade Headquarters Company and the 562d EBM Company spent their first week in Australia at Camp Cluden, a “delightful” staging area just outside of Townsville. The predominiating feature of this camp was the depth and softness of its mud, and the force of the torrential rains. Never had the Amphibs seen so much mud in such a small area. Their “pleasant” week at Cluden was followed by a few days of enjoyable travel through “sunny” Queensland from Townsville to Rockhampton on one of the narrow-guage “Aussie rattlers”. With the exception of the 532d EBSR, the remainder of the brigade established itself in an area extending from a point twelve miles north of Rockhampton, Queensland, to the coast. In both of these locations it was necessary to carve campsites out of virgin territory. Less than a week after their arrival the news was circulated that someone had heard their new radio “friend”, Tokyo Rose, broadcast a welcome to “the three new amphibian regiments and service units in Australia.” “We will come over to see you one of these days,” she added. They never did. Instead we soon headed to “see” her.

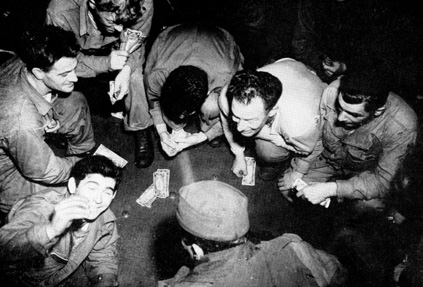

Aboard the “SS Noordham” going overseas. February 1943.

Favorite indoor sport quickly passes the time (and money)

for all concerned.

The Amphibs were enthused and anxious to go immediately into combined training with Australian and other American troops, but got a rude awakening when they found no landing craft available. The fine assembly plant at Cairns where hundreds of landing craft were to have been ready just did not exist. The boat assembly unit had arrived early in December only to find the building which was to house their plant not even started and the site still encumbered with an old sawmill whose owners were holding out for a higher settlement. On top of this, the transports bringing the equipment and knockdown landing barges seemed to vie with each other in arriving at separate ports. It was many weeks before the equipment was sorted out and finally delivered over the rushed Australian railways to the plant so production could get started.

Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia. April 1943.

General MacArthur and Lt. Gen Eichelberger inspect the

542 Regimental Area. Col Fowlkes and Lt Col Simpson

escort our distinguished visitors.

Until boats could be made available to them, training in the regiments was principally in infantry tactics with particular emphasis on jungle fighting. Equipped with the new jungle uniforms and kits, troops were taken on bivouac into the Australian bush country for periods of a week or more, during which time they carved their way through jungle terrain, executed jungle problems, slept on jungle hammocks, and subsisted on jungle rations. Schools were also conducted for the training of Amphibian Scouts in their job of making a reconnaissance of hostile beaches and of slipping stealthily ashore in advance of an operation to install beach markers and otherwise facilitate the landing of the first boat waves. Classes and practice in anti-aircraft firing, aircraft recognition, signal communication, boat maintenance, water-proofing of land vehicles and in the use and maintenance of the amphibian vehicles formed an important part of the training period for the rest of the brigade. Meanwhile the shore units were given specialized training in such work as laying matting for beach roads leading from the beaches. Experiments were also conducted at this time in the use and effectiveness of the new 4.5-inch secret barrage rocket.

While this training was in progress both at Rockhampton and at Cairns, the 562nd EBM Co. and men of the 532nd EBSR pitched in to help the 411th Engineer Base Shop Battalion set up their boat assembly plant at Cairns. They worked twenty-four hours a day, mostly in the heaviest tropical rain and mud. On one fine day early in April, 1943, they had the satisfaction of launching their first LCVP, a landing craft destined to land combat troops on enemy shores. Soon seven completed boats were daily coming off the three mass production assembly lines. The brigade took on new life as the boatmen got back to the throttles and began to learn about this new type of craft which differed in many respects. from those they had operated in the states.

Now the brigade had to make another rail shipment of LCVPs, all the way from Cairns to Rockhampton, six hundred miles. With the narrow gauge Australian railways and their small flat cars, this was no easy job. With only inches to spare on horizontal and vertical clearances, the train load of nineteen LCVPs finally reached Rockhampton. This trip contrasted strangely with the 150 boat movement in October 1942 from Cape Cod to Carrabelle on the American railways.

It was at this time that the brigade almost got its first combat mission. Late one night in March, Sixth Army called General Heavey on the Secraphone (this phone cannot be tapped) and was asked how many combat troops he could alert to be moved to the west coast of Australia. It appeared one of our aviators had observed a Jap invasion convoy heading for Australia. There were very few combat troops in Australia at the time to meet such an attack. Our shore battalions and headquarters units at Rockhampton were quickly outfitted and reorganized as infantry and all plans made to move on short notice. However the Jap convoy evaporated into thin air and a few days later the alert was lifted.

Early in April the brigade was honored with a visit by the Theater Commander, General Douglas MacArthur. His interest was centered mainly on the operation and effectiveness of the new types of Amphibian equipment. He climbed aboard a DUKW and, after a short trip in and out of the surf, he appeared favorably impressed with its possibilities in amphibian work. He witnessed a demonstration of boat and shore operations and exhibited a keen interest in the accuracy of the timing. He devoted much attention to the range and effectiveness of the rocket firing. The friendly manner in which the General talked with the officers and enlisted men alike caused many a heart to beat faster that day. Bursting with pride, the fortunate few with whom he had conversed wrote home that they had talked with General MacArthur and then joyfully shook hands with their buddies who sought only to “shake” the hand that shook the hand --- ---- ----.”

During the next few weeks, preparations were made for a large-scale demonstration of special equipment and tactics employed by the Amphibian Engineers. This demonstration, which was staged late in April on a beautiful beach near Yeppon, Queensland, was attended by a distinguished group of high-ranking U. S. and Australian officers, including Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, Commanding General of the Sixth U. S. Army; Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, Commanding General of I Corps; Brigadier General (later Major General) H. Casey, Chief of Engineers, GHQ; Major Generals Berryman, Vasey, and Dewing of the Australian Army; and Colonel Wong of the Chinese Army. Emphasis was placed on the work of the Amphibian Scouts and the use of the barrage rocket. They were brought to a point several hundred yards offshore in a small boat (simulating a submarine), and from there, they swam ashore towing a supply of provisions in a floating jungle pouch. Under cover of a smoke screen, LCVPs landed infantry troops on the beach. A simulated air attack was staged and machine gunners on the boats successfully warded off the “raiders.” The shore engineers landed on the second wave and set up machine guns, decontaminated gassed areas, exploded land mines, laid road matting and removed obstructions. The DUKWs were used to bring ashore materiel and supplies of all classes, direct to the dumps established back of the beach. The climax of the demonstration was the firing of rockets from a DUKW at a target on Bluff Rock, an island fifteen hundred yards off the beach, under the direction of Major Volgenau. Two ranging rounds were fired and the fire-for-effect salvo landed squarely on the target, demolishing it completely. This was the brigade’s first large-scale show in Australia and caused favorable comments about the latent possibilities of such a unit in combat.

Rockhampton, Australia, March 1943. Co E, 592 EBSR returns

after living one week in the jungle testing special jungle equipment.

Early in July, 1943, the brigade began using its present appellation of “2nd Engineer Special Brigade” and the regiments became “Boat and Shore Regiments.” The word Amphibian was entirely deleted from the name. There is no explanation of why the word Special was substituted in place of Amphibian, but it is thought that it was done for the sake of secrecy. All brigade units, with the exception of the 542d EBSR, moved to Cairns, Queensland, in June 1943, for better combined training with the Australians and U. S. Navy. Upon arrival the Brigade Headquarters divided itself into an advanced operational echelon and a rear administrative echelon. The Navy sent an amphibious staff under the command of Rear Admiral Daniel Barbey (“Amphibious Dan”) to Cairns, and with them the brigade established a joint headquarters for close cooperation in the combined training off Cairns and in preparation for coming operations in New Guinea. At this time the 562d EBM Company was reorganized and expanded into the 562 EBM Battalion. Realizing that successful operations would be in direct proportion to the efficient maintenance of our landing craft, General Heavey, in his thorough long-range planning, had insisted on this expansion. The new plan allowed a complete Boat Maintenance Company to go with each regiment detached from the brigade for special missions.

The process of reorganization and the movement of the additional brigade units from Rockhampton to Cairns did not hamper the training program that was already under way by the 532d EBSR with the Australian troops. The Aussies were anxious to get into the fight against the Japs who were already threatening the northern shores of their homeland. When the Amphibs heard that they were going to work with the famous 9th Australian Division (the “Rats of Tobruk”) in impending amphibian operations in New Guinea, they took hold with renewed vigor and determination. These veteran AIF troops who had performed so admirably in the defense of Tobruk against Nazis, Fascisti, and desert sands had won every Amphib’s confidence long before actual training began. In the very waters where Zane Grey had deep-sea fished off Cairns they sought to gain the 9th “Divvy’s” confidence by demonstrating skill in boat operation by delivering them safely and on time on strange but correct beaches after an all-night trip in darkness and fairly rough seas. It was not long before the Yank and Aussie staffs were talking with the same terms, we Americans becoming familiar with their organization, abbreviations, and tactics, and they with ours. Several officers and men were sent to live and work with the Aussies and they reciprocated by sending men to our units. The men of the 2d Brigade soon learned that “bloody” did not necessarily mean spattered with gore, and the Aussies learned that certain American appellations became terms of endearment - rather than a reflection on one’s ancestry - when said with a smile. Their Commanding General, Lieutenant General Sir Leslie Morshead, said, “We must have no secrets from each other”. “We must show each other everything we have in our pockets.” This is exactly what was done.

The 532d EBSR and the 9th Australian Division cooperated in practice maneuvers on Trinity Beach near Cairns daily until the 532d departed later in July for their advanced base at Morobe on the north shore of New Guinea. The 592d EBSR, which had established itself in Cairns by this time, continued to carry on these practice maneuvers with both the 9th and then later the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions, while the 542d EBSR continued such limited boat training as was possible with the boats available in the Rockhampton area.

From the early part of May until late September, one brigade unit after the other was on the move from Australia to New Guinea. At first, because of the scant supply of landing craft, just small detachments were formed and sent north to perform specific missions and to “feel out the situation,” but as the Cairns assembly plant gradually increased its production to thirty and forty boats a week, these detachments were expanded until they finally embraced full companies and battalions. It is hard to believe that the 2d ESB was less than a year old when it got its first taste of combat, but their first year was replete with thorough and intensive combat preparations. Now the aspiration of every Amphib “to get into this mess and help clean it up” was at hand.

Except for a few lucky furloughees who got down to Sydney a year or so later, the happy days spent in Australia were over. The brigade was Guinea bound! The first important step in the road to Tokyo!

|