Chapter XI

On To Corregidor

JUST a little over a month after the successful invasion of Mindoro, we were off again to make another assault - this time on the shores of heavily-fortified Luzon Island. The primary objectives of the Luzon Campaign were the recapture of Manila and Corregidor which had fallen to the Japs on 2 January and 6 May 1942 respectively. The gallant defense of Corregidor by American and Filipino troops under Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright will never be forgotten. When it fell, every American soldier, sailor, and marine no matter where he was stationed firmly resolved that someday somehow the stars and stripes would again fly over that island fortress to avenge the honored living and dead who had struggled to their utmost to preserve that symbol of freedom and liberty of the Filipino people.

"On to Corregidor!" became our battle cry. The road back had not been an easy one, but now after two and a half years we were standing on the threshold of the fulfillment of our resolution. Luzon Island, with its bastions of Manila and Corregidor, was out next objective.

Prior to our "official" entry into the Luzon Campaign, troops of General Walter Kruger's Sixth Army were landed on the shores of Lingayen Gulf. In a sense we also participated in that landing because the eight barges of "Lt. Snell's Odyssey" as described in a previous chapter were taken to that beachhead.

The 592d EBSR under the command of Colonel Allen L. Keyes with two attached brigade units, Company A of the 262d Medical Battalion and the 1460 Engineer Maintenance Company of the 562d Engineer Boat Maintenance Battalion, represented the brigade in this campaign by participating in fifteen separate amphibious landings on the shores of Luzon. Vigan, a village on Luzon's northwest coast, was selected as the first point of attack, but in the usual manner this operation was called off just as the regiment had resigned itself to the hustle and bustle of another move. Still in the usual fashion, another mission suddenly appeared on the books. The amphibious attack would be made near the barrio of La Paz just north of Subic Bay. After a long-to-be-remembered mad week of hurry and scurry and backbreaking work loading out most of the Task Force and then its tired self, the 592d settled down on 25 January 1945 for a little shipboard rest as they sailed from Leyte to Luzon.

The trip was quite uneventful, for the expected attacks by Jap suicide planes and possibly submarines never materialized. The weather was even in our favor. Time on shipboard was spent in studying charts and air photographs of the beaches and in planning the attack and later shore operations. However, there was still plenty of time left to enjoy the good food, books, and card games.

The famous "Bloodless Landing" on the beaches near the barrio of La Paz on the west coast of Luzon took Place on 29 January. At dawn the assault landing craft bad been launched from the transports and troops were going over the sides of the big ships and down the cargo nets. The first wave hit the beach at 0830 and it was with pleasant surprise that the men were greeted with Filipino cheers and American flags instead of expected enemy fire. The men will long remember the deep, coarse, loose sand on Red and Blue Beaches and how the Shore Battalion cursed and groaned dozers into miraculous work until the Navy's eyes popped at the unloading record set up by the 592d in those two hectic days. At La Paz, Colonel Keyes and his Regimental Headquarters were located in the school building in the barrio. The Shore Battalion squatted along the beach, and the Boat Battalion set up camp on the village green. The first look at Luzon was not too discouraging but this stop turned out to be a short one.

A three-day stay in La Paz found the job completed and their next destination was established as "somewhere around Subic Bay." Major Frank L. Mann was dispatched posthaste to choose and lay out the new camp and Captain Seymour G. Lederer of New York City was sent out to reconnoiter the roads and bridges that would be used by his overland convoy in moving to the new area. On the first day of February, as the floating stock of the regiment set out on the cruise to Subic Bay, the Shore Battalion vehicles were formed into convoys and once more the 592d was on the move.

The spot chosen for the new camp had been in peacetime a rifle range operated by the United States Marines. It was located halfway between the towns of Subic and Olongapo on the shores of beautiful Subic Bay. The sloping green hills only a short distance inshore gave the camp area a sort of primeval beauty. The Boat Battalion was camped a short distance away from the rest of the regiment in a coconut grove which was their pride and joy. Major Mann had done his work well, and after several days of arguing with the company commanders he even succeeded in getting the mess halls in one straight line. The regiment occupied this camp from February through April, and, since Manila Bay was not yet open, much lighterage work was done at that base. Here the men also got their first real taste of Filipino social life, customs, and, of course, liquor. Visits to the surrounding towns were an almost nightly occurrence. A sure sign that the Amphibs were out of New Guinea at last came when several of the men ventured opinions in favor of marrying and settling down in the Philippines. The stay at Subic Bay was one of the richest periods in the history of the 592d Regiment. It was from this camp that some of the best known missions were run. Only years in the Army can develop the humor with which the boatmen and shore engineers left Subic on the backward trail to La Paz to bring up the supplies and ammunition that they had so recently unloaded at that location. The trials and tribulations of the Boat Battalion with their water taxi service to the ships in the bay, Captain Charles C. Ferrall's nightmarish beachtower in the form of a Chinese pagoda, the "No Labanderas in the Area" sign, and the "on pass" trucks to Manila through Zig-Zag Pass all bring fond memories of old Rifle-ran Beach.

The battle for the opening of Manila Bay was now in full swing and on 15 February 1945 the 592d started to contribute its share when the first Task Group "A", which was composed of Companies A and F with attached personnel, moved down to Mariveles at the foot of the famous Bataan peninsula. This group was under the command of Major Henry M. Seipt. The landing at Mariveles was delayed for a few hours because the Jap shore batteries managed to drive off the Navy minesweepers. They were soon silenced by Naval gunfire and the assault continued. Of the six LCMs in the convoy, five were loaded with 592d equipment and personnel. On entering the harbor the sixth LSM struck a mine and the resulting explosion killed over forty men and destroyed much valuable equipment. We were fortunate once again in that no Amphibs were on that particular LSM. First Lieutenant Albert Cappelli and his boat wave returning from the beach rescued many of the survivors. T/4 Joseph R. Crummie, Company B, in LCM 713, which was one of the boats in Lt Cappelli's wave, pulled alongside the burning ship and did outstanding rescue work.

When the boats finally moved into the beach, the approach proved to be so shallow that the LCMs grounded fifty yards from shore while the LSTs and LSMs were "beached" at the one hundred yard mark. That gave the shore party a real unloading job. The 592d message center personnel did fine work in this operation. The weapons carrier on which their SCR 193 was loaded dropped into an underwater bomb crater just before it reached the beach soaking the radio in salt water. Immediately the radio men stripped the radio, rinsed the parts in fresh water, dried them out, and soon had the station operating. In spite of this ducking and the fact that the tactical situation necessitated moving the location of the radio station three times in the first two days, the station was closed for a minimum length of time.

On the morning after the Mariveles landing, Task Group "A" sent twenty-five LCMs to participate in the assault on Corregidor. Leaving Mariveles early in the morning they landed parts of the 34th RCT "on the Rock" at 0830. The value of right living was well shown on this job because the opposition and obstacles were never tougher. All waves encountered heavy machine gun fire from the caves along the beach and many hits were scored on our LCMS. One barge turned up with forty-eight bullet holes in her hull, but only one below the waterline. T/4 Joseph Kaplan of Richmond Hill, New York, was shot in the stomach and died the next day. Five other boatmen were wounded but fortunately all survived.

The Navy did not know whether or not LSMs could land on Black Beach on Corregidor, so Colonel Keyes offered to take in the crash boat "Cotuit" (now the "Sweeney") and find out. 1st Lt Paul C. K. Smith of New York City was at the helm during the reconnaissance. Criss-cross machine gun and small arms fire from the beach raked their course, but T/4 Thomas Benedict of Bay City, Texas, flanked by Colonel Keyes and Lt Colonel Tucker, stood on the bow casting the leadline and they got in and out again with the desired information. T/4 Robert Collins of East Hampton, New York, and T/5 Howard B. Calkins of Bangor, Maine, were at their twin fifties during the run.

The Shore Party on Corregidor also did a wonderful piece of work. An example of the beach conditions on Corregidor may be seen from the work of Sergeant Ira E. Reed, Company F, of Kerns, Virginia. Under the flanking fire from small arms and machine guns which were located in caves on either side of the beach. Sergeant Reed was directing his men in their task of unloading bulk stores and vehicles from the landing craft. They did not seem to be making much progress, for the heavy water distillation units and other trailers without prime movers were presenting a particularly difficult problem.

"If we only had a bulldozer," he said to himself, "we could get those things off of there in jig time."

He looked up and down the beach. All the other dozers seemed to be busy. Then he spotted one that was apparently idle. He was in luck, but look where it was - fully exposed to enemy fire and in the middle of a Minefield where six other vehicles lay in wreckage sat the dozer. Maybe he could get it out and maybe not. He felt it was worth the try. Picking his way across the mine-strewn beach, he was subjected to a renewed burst of enemy fire, but that did not faze him. Reaching the dozer, he climbed aboard and as rapidly as possible he got it started and withdrew to the beach. With the help of this equipment the unloading was speeded up and the landing craft were able to retract a short while later.

As all waves came into the beach they were riddled with enemy machine gun bullets from the left flank. The beach itself seemed to be exploding as vehicles unloading from the LCMs set off land mines buried in the sand. LCM 474 of the first wave ran into trouble on the beach when the crew could not raise the ramp. They were having difficulty trying to back out of range when T/4 Clyde Hyatt, Company A, coxswain of LCM 685 in the second wave spotted the distressed barge. In spite of the heavy enemy fire, Sergeant Hyatt moved in and took the disabled boat in tow getting it safely out to the maintenance barge.

The trials and tribulations of being an Amphibian were again well illustrated when the fifth wave hit Black Beach On the approach to the beach the boats were running parallel to a high rocky cliff which extended out for about seven hundred yards. LCM 734 was the left flank boat and was an ideal target for the Jap machine gunners. By the time 734 hit the beach there were several holes in her hull and some of the infantrymen in the well deck had been wounded. There were land explosions on the beach as vehicles coming off the boats hit land mines and blew up. The coxswain of 734 called repeatedly for the vehicles on his boat to unload but neither of the two jeeps moved. Apparently the driver of the first jeep had been hit because he could not be found. PFC Robert J. Meheran, Campany A, Hartford, Connecticut, was still at his post behind the twin fifties, but realizing that his boat was blocking the narrow beach and endangering lives, he jumped into the first jeep and drove it off the ramp. Returning to the ramp he was thrown to the ground and wounded by a terrific explosion behind him. The driver of the second jeep had hit a land mine. Both vehicles and the other driver were blown up in the explosion.

T/4 Gerard Cavan, Hq Co Shore Battalion, of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, had charge of the Communications Section for the Shore Party which landed on Corregidor. Though under intermittent rifle and automatic weapon fire from well concealed enemy positions surrounding the small beachhead, the party immediately opened up in the 610 radio net and stayed in twenty-four hour contact with Mariveles for the duration of the operation. T/5 Frederick H. O'Neil, also of Hq Co Shore Battalion, of Binghamton, New York, was killed by enemy fire on the second day and for thirty-six hours, Sergeant Cavan operated the radio until another relief operator could be sent over from Mariveles.

It was soon after the landings on Corregidor that Lt Colonel Tucker and his Survey Unit had all their fun. Late in February the unit was proceeding to Orani to survey the harbor there. About a mile from Corregidor they picked up a Jap who was floating around on a log. The Jap, upon being searched, struck T/3 Glenn Cornett, Hq Co Boat Battalion, of Anco, Kentucky, several jui jitsu blows. Cornett quickly "subdued" the Jap and the party proceeded.

About noontime the survey party observed a long canoe-type boat which was trying to avoid mortar fire from shore. It looked like an enemy barge, so Lt Colonel Tucker, T/3 Robert E. Rhodes, Company B, of San Francisco, California, and T/5 John F. Buggie, also of Company B and from St. Joseph, Michigan, attacked the boat in their LCVP. Five Japs jumped into the sea but the remaining occupants continued to fire at the oncoming LCVP. These five were picked up and the battle suddenly ended when the other Japs destroyed themselves with two hand grenades.

On the way back to Mariveles this same party found three Japs on a raft off Pilor. The Japs refused to surrender and, since ammunition was getting a bit low, the problem was solved by ramming the raft with the LCVP. Only one Jap rose to the surface - and he did not live long. They next sighted twenty Japs swimming in the sea about a mile off Corregidor. These Japs were "rescued" with comparative ease. Colonel Tucker and his party returned to Mariveles with a total of twenty-six prisoners to show for their day's work.

On 25 February two of our LCMs were swinging around Corregidor when they saw a smoke grenade go off in the vicinity of Wheeler Point on the "Rock". Since this was a prearranged signal for distress, the boats moved shoreward to look over the situation. They found a paratroop patrol fighting furiously but pinned on the beach, which offered little protection from the heavy machine gun fire coming from the heavy brush and caves on Wheeler Point. One LCM headed full steam for the beach while the other remained offshore to cover her approach. By this time the enemy fire was now directed at both barges as well as at the patrol on the beach. The shoreward bound LCM under the direction Of T/5 Stanley Jarris of Beacon, New York, made its way through water infested with “niggerbeads” and with partially submerged rock reefs. Then it happened. A heavy swell lifted the barge and dropped it fast on a jagged rock. The other LCM of Company A, crewed by T/4 Raymond E. Enos of Cudahy, Wisconsin, PFC Paul T. Clifford of Oil City, Pennsvlvania, T/5 Hershel W. Hall of Jackhorn, Kentucky, and T, /5 Jordon C. White of Texarkana, Texas, moved in under concentrated enemy fire and pulled the damaged craft off the rock. Its bilge pump kept it up. Then both boats went ashore and hastily took aboard the besieged paratroopers, well and wounded, and got off the beach successfully.

The fight for Corregidor continued for a few more days until finally all enemy resistance was overcome. One objective of the Luzon Campaign had been accomplished the stars and stripes were again flying over Corregidor. The detachment of the 592d Boat and Shore Regiment that had performed so admirably in the capture of that fortress was awarded by direction of the President a Unit Citation on 8 May 1945. "Their magnificent courage, tenacity, and gallantry avenged the victims of Corregidor of 1942, and achieved a significant victory for the United States Army." This was the Brigade's third Presidential Unit Citation, an honor of which every brigade member will be forever proud.

While the main body of the 592d Regiment was engaged in the Luzon area, Company C of that regiment was completing its missions around Ormoc, Leyte. They had had a pretty rugged going in that area and as a result of losses over a period of time were running short of officers. However the Brigade got orders to prepare this boat unit for a landing with the l1th Airborne Division at Nasugbu on the west coast of Luzon south of Manila Bay. 1st Lieutenant John H. Kavanaugh was placed in command of the first echelon of Company C to head for Luzon. This echelon of 21 LCMs in convoy with six FS boats, two destroyers, and three subchasers left Mindoro on 3 February and arrived at Nasugbu in Batangas Province on Luzon the next day. They found a good anchorage near the Wawa River Estuary and bivouacked there. At Nasugbu the detachment was attached to the l1th Airborne Division. The remainder of the company under the command of 1st Lt (later Captain) Kenneth R. MacKaig followed, arriving on 10 February. Their work at Nasugbu consisted primarily in the unloading of FS boats but their chief pastime was the capture of Jap Q-Boats. On St. Valentine’s Day the Nips staged a Q-Boat attack on the C Company anchorage, but expecting something of this sort, Lt MacKaig had previously constructed log booms which proved to be a bit too rugged for the plywood boats. During their stay at Nasugbu Company C ran up its total of captured Q-Boats to seven. Since some of them-were in pretty fair shape, Q-Boat racing became one of their favorite sports.

One of the many incidents at Nasugbu will live a long time in the minds of the men of that detachment. On the night of 20 February a Spanish landowner from the district came to the Company C bivouac area and asked Lt MacKaig, the Company Commander, if he would send boats to the town of Calatagan some forty miles to the south. It seems that that barrio had long been a refuge for a large number of white people who had fled from Manila to escape the oppressive rule of the Japs. They had drifted south and settled in this sleepy peaceful countryside barrio that was in peacetime a favorite resort by virtue of its location in the center of a hunting preserve. The landowner said that his men had reported to him that the Japs in that area had orders to kill all white people on sight and that already the search was on. He added that his aged mother was in the apparently doomed group and also that attempts by Yank forces and guerillas to pass the Jap roadblocks had failed. Unless help from the sea could be rushed to them immediately, they would surely be annihilated.

A few days later on the 25th of February a strange 592d rescue convoy set out from Nasugbu. Lieutenant MacKaig was leading in the control boat, the "P-9", which was a Veteran of many an assault landing. Next were two LCMs equipped with extra life jackets, rations, water, litters, and medical aid men. The "Susfu Maru", a flak LCM under the command of Lieutenant Kavanaugh and the rocket LCM 292 under 1st Lieutenant (later Captain) Edwin T. Stevenson trailed along behind for rear protection. Picked riflemen were on each LCM to take care of sniper or Q-Boat attack. A Filipino courier had been dispatched the previous day with instructions to the civilians. Utmost secrecy was necessary for obvious reasons. A large American flag was to be waved on shore if the civilians were ready and plans had not been discovered. The civilians were to stay bunched together and sightseers kept away so as to allow greater freedom of fire from our weapons.

As the convoy approached the stricken area they could easily discern a small group, of white people on the beach wildly waving the American flag. The coast-was clear. Quickly the craft disposed themselves according to prearranged plans. The "Susfu Maru" and the rocket LCM took up positions covering the approaches of a long winding channel, for enemy machine guns were known to have been set up along these approaches. 1st Lieutenant Joseph J. Blumberg of Queens Village, New York, then maneuvered his LCM through the narrow reef-studded channel while the second LCM was sent out beyond the range of small arms fire to stand by as the safety boat. The picket boat moved back and forth directing all movement by radio and ready to add her fire to any critical spot. All men and officers literally held their breaths while Lt. Blumberg's LCM made the channel at dead slow speed. “She was just a sitting duck with no room to maneuver in case of attack. The beach was finally made without a shot being fired, the ramp lowered, “ - and the refugees entered the barge among scenes that will never be forgotten.

Aboard the first LCM was a man we shall call "Colonel Mac". He was a member of General MacArthur's Staff and had been evacuated from Corregidor before its capture by the Japs in 1942. Colonel Mac's wife was among the group of refugees and he was standing on the catwalk near the ramp eagerly searching the crowd when he saw his wife smiling at him. For three long years they had waited for that day. Meanwhile, people of all nationalities quickly came aboard. Instead of the expected fifty people there were ninety, so Lt James E. Klug went in with the second LCM and picked up the remainder.

Still amazed at receiving no fire and by way of celebration, Lt Kavanaugh and the crewmen on his "Susfu Maru" fired a few rounds at a Jap lugger stranded on a reef and set her afire. In the meantime Lt Stevenson and his crew shot up and set ablaze two Jap Q-Boats. While this was going on, the civilians held their own celebration with the rations, especially the canned cheese which they had not tasted in several years.

It was later discovered that the Japs did have positions on all approaches to the beachhead but had taken off when they saw the landing craft heading into shore. They had flashed the word that an assault landing was being staged and, mindful of the bombardment that accompanies most of the Yank landings, the Jap Headquarters had even moved their CP further into the hills in an effort to hide from the hated Yanks.

The great versatility of Amphibians was never shown to better advantage than by the varied activities of the 592d Task Group at Legaspi on the southeastern tip of Luzon. This was another city in the province of Batangas which fell under the spell of the 592d. On April Fool's Day of 1945, Major Henry M. Sept and his force composed of Company D and one platoon from B Company landed the 158th RCT and again found the Japs a minus quantity. Soon after they landed, the group got the job of salvaging and operating the remains of the old Legaspi-Manila Railroad. 1st Lieutenant Frank Trumbly of Burbank, Oklahoma, was Operations Officer in charge of the new enterprise. With fourteen men to help him, Lieutenant Trumbly began the job with little of no experience, one questionable locomotive, a twisted track studded with bomb craters and small rolling stock of ancient and battered cars. Staff Sergeant Alex G. Smith of Elgin, Texas, was able to round up a working crew of two hundred Filippinos who had at least seen a railroad before and with Company D men supervising the job, ties and rails were salvaged from sidings to repair the main line. Dilapidated cars and the tired old engine were repaired. In less than a month the line was operating over a distance of forty-two miles. The inaugural run was almost ruined by a group of snipers. The train was derailed on the second trip right in the middle of a skirmish with a by-passed pocket of Japs. Somehow the boys got it back on the track and beat a hasty retreat. "Seipt's Short Line Serving Southern Luzon" finally consisted of an engine and tender, a hospital coach, capable of accommodating fifty litter patients and a hundred walking wounded, a reefer car for perishables, a caboose unbelievably equipped with a kitchen, and forty flat cars. Men from Company D operated the railroad. PFC Willie L. Ballowe of Richmond, Virginia, was the engineer. Corporal Warren G. Keough of Turtle Creek, Pennsylvania, and PFC Harry F. Canese from Brooklyn, New York, were dispatchers. The railroad even boasted a station master in the form of Private Michael Fitzsimmons of Brooklyn, New York. Everyone said that, with a Brooklyn dispatcher and station master the "Short Line" could not help but be a howling success.

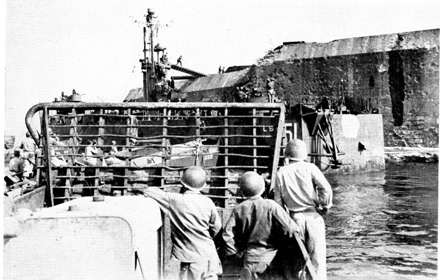

Caballo Island, Luzon, Philippine Islands. 28March 1945. Co. A,

592 EBSR, LCM lands infantry on rock bound beach of Jap held

island.

The second versatile move came when the Amphibians became field Artillery men to help out the 158th RCT. Out of the estimated enemy garrison of eight thousand troops stationed around Legaspi, the majority were either killed or had been pushed from the area. However, about fifteen hundred of them were caught in a basin at the top of the heights just behind the town and were surrounded before they could escape. But as often happens in such cases, the catch provided a first class problem. Hiding down in a natural depression, the Japs were safe from direct observation and the rim of hills around them provided protection from flat trajectory artillery fire. The Commanding Officer of the 158th had been very much impressed by the firepower put out by the rocket LCM at the time of the initial landing. He recalled all the hell they were able to raise and wistfully remarked, thinking aloud, how nice it would be if the Japs were within range of the boats. As that was not possible the next best thing was to take the rockets to them. By working feverishly all day on the l0th of April the maintenance men were able to remove three rocket launchers from the rocket LCM and weld them on the bed of a weapons carrier truck. The contraption was test fired and, except for the backflash setting off the dry grass at the rear of the truck, was pronounced satisfactory. Master Sergeant Frank C. Holton of Richmond, Virginia, Private Bertram E. Higgins of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Private Leroy Stephens of Indiana. all of Hq Co Boat Battalion, were detailed as a crew for the new weapon. Loading up the racks, and with a reload behind in a trailer, the Amphibians took to the hills. After marking it out on the map and scouting it in a jeep, the men pulled into their first position and set up for business. Private Higgins pressed the switch and the first batch of thirty-six rockets went sailing over the coconut trees into the Jap retreat. During the next thirty days they made several trips and fired a total of over six hundred rockets. An indication of their effectiveness was given by a Jap lieutenant who was captured on 7 May just a few days before the occupation was completed. According to him a whole platoon including the officer in charge was wiped out the day before by what they thought was mortar fire, when they left cover to scout out an escape from the pocket. But the 158th RCT had fired no mortars that day and the 592d men had delivered on especially heavy rocketload.

Ft. Drum (El Fraile Island) Manila Bay, Luzon, Philippine Islands.

13 April 1945. Fort Drum, the “concrete battleship”, going up in

smoke. Flame oil was pumped into the Fort from LCMs of Co. A,

592 EBSRand then ignited by incendiary grenades.

Batangas, Luzon, Philippine Islands. May 1945. Men of

Regimental Headquarters, 592 EBSR

Meanwhile the Task Group was continuing to run daily and nightly missions around the Legaspi area. On one occasion they took a mission to Libog to evacuate an infantry platoon. They encountered no opposition but did hit some Jap underwater obstacles consisting of barbed wire and poles. Luckily the resulting damage was negligible and every mission was successfully completed. Later dates saw assault landings at Rapu-Rapa, Karoghog, Batan Island, and at Bulan so the men managed to keep busy with very little trouble.

Batangas, Luzon, Philippine Islands. May 1945.

Officers and men of the 592 EBSR Motor

Maintenance Section.

Batangas, Luzon, Philippine Islands. May 1945. Officers

of the 592 Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment.

On 27 March 1945 Company A took a crack at Caballo Island which lay a short distance from Corregidor and more or less a guardian of the entrance to Manila Harbor. Caballo Island, in the usual Japanese fashion, was honeycombed with caves and tunnels and because of this the American troops were on the 3rd. of April completely stalemated in their attempts to get the Japs out of the recesses in the island's surface. The success of the operation hinged upon the construction of a super-flame-thrower. Again the 592d was called upon. LCM 503 was chosen for the task and work was quickly started on her. Fuel tanks were installed giving the LCM a capacity of thirty-four hundred gallons. Along with this a powerful pump capable of throwing five hundred gallons a minute was secured and connected to the tanks. The tanks were filled with a mixture of three-quarters diesel fuel and one quarter gasoline. At 0815 on 5 April the Task Group landed on George Beach directly under the cliff on Caballo Island. The engineers started to work and by 1300 that day had laid eight hundred feet of four-inch pipe to a height of 175 feet from the barge up and over the cliff. The Japs on Caballo were firing mortars and sniping at the boat all the time it was on the beach. The sea was rough and the beach rocky, but in spite of these conditions and the Japanese fire, the LCM was held on the beach without once breaking the pipeline. On the first day twenty-three hundred gallons of mixed fuel was pumped into a cave. An incendiary grenade ignited this and the resulting explosion showered the LCM with debris from the cliff. On the second day a similar performance was staged. But on the third day, six thousand gallons of fuel were pumped into an opening and a larger demolition charge was used. When this exploded, it blew up a hidden Jap ammunition dump and the resulting explosion practically tore the cliff apart.

Landing engineers on Fort Drum to lay hose to pump from flame

throwing LCM

Bantangas, Luzon, Philippine Islands.

April 1945. Shows beach operated by

592 EBSR for the Base. Shore

Engineers direct unloading Boat

Battalion LCMs.

The assault on Fort Drum in the middle of April gave the Amphibians another chance to show their wares. Fort Drum, erected on El Fraile Island, was a huge battleship shaped concrete fort in Manila Bay and getting the japs out of it looked like an almost impossible task. An LSM was furnished by the Navy and a swinging ramp was erected on top of the conning tower to serve as a bridge to Fort Drum. Thus the engineers were able to board the fort like the pirates of old boarding a prize. One LCM was chosen for a stand-by boat while four LCVPs were assigned the task of holding the LSM and another LCM equipped with fuel tanks and pump against the fort. while operations were tinder way. The plan of attack called for the lowering of a five-hundred pound charge of TNT with a half-hour fuse into the fort and then have the LCM pump fuel into the fort while the fuse was burning. The hose was laid without much trouble, the charge placed in the fort and the fuse ignited. The sea was, as usual, rough and the crew of the LCM was trying to assist the LSM so that she would not smash her bow on the fort. At the same time they were trying to hold the pipeline in place. As soon as the fuse on the five-hundred pound charge was ignited, pumping of the fuel into the fort was started. Then the fuel line broke! A man was immediately sent up to cut the fuse and the line was hauled back into the LCM for repair. When the pipe was re-laid and the fuse re-lighted, pumping operations began anew. However, the Occidental rupture of the fuel line had necessitated the cutting of about ten minutes of the burning time from the fuse line. Now speed was of paramount importance. The LSM recalled all the infantrymen from the fort and withdrew, but the LCM stayed up against the fort and pumped her tanks dry before leaving. She pulled away as rapidly as possible but was only about four hundred yards away when the fort blew up. Two days later the concrete of the fort was still so hot that no reconnaissance could be made. The crewmen of LCM 503 that carried out this operation were T/4 William Griffin of Centerville, Alabama, as coxswain; T/5 Robert Holmes of Mount Lebanon, Pennsylvania, engineer; and PFC John W. Chaffe of Richfort, Vermont, seaman-gunner. The fourth member of the crew, T/5 Rex Hammond of Columbia, South Dakota, had been hospitalized on Corregidor after the first day on Caballo Island where this same LCM was used.

The 592d were then assigned the task of landing the 151st Infantry Regiment on Carabao Island at the entrance to Manila Bay and just a short distance from Corregidor. There was no beach on Carabao Island, At the spot chosen for the landing there was a concrete sea wall ten feet high and six feet thick. The plan called for the breaching of the sea wall before the landing. The boatmen of Company A stationed at Subic Bay drew this mission. Three days prior to the assault they landed artillery men on selected positions along the south shore of Manila Bay from which point they could lay harassing fire on Carabao Island and contribute to the pre-invasion bombardment on the day of the landing. When that day arrived, the island was first bombed and strafed by medium bombers while the cruiser Phoenix, two destroyers, and two infantry landing craft with rocket launchers shelled the sea wall and the facing cliffs. 1st Lieutenant Minton Clute of Detroit, Michigan, took the first wave into the beach at 0930 and found that the sea wall had been breached but that the beach was not suitable for vehicles. Opposition to the landing was light but a tremendous explosion of unknown origin occurred about an hour later causing many casualties. The troop commander ashore requested a LCM to make a reconnaissance of the southern part of the island and to investigate waterline caves. 1st Lieutenant Thomas Stafford of Charleston, South Carolina, and Sergeant Norbett Van Graafeland of Spenceport, New York, volunteered to take two LCMs for the job. They made a complete circle around the island and approached to within twenty yards of the cave entrances without drawing enemy fire. Carabao Island was soon in American hands.

The 592d's "Inland Navy" should not be forgotten in recalling those days on Luzon. "Laguna de Bay" is a large freshwater lake lying southwestward of Manila Bay with which it is connected by the Pasig River. This lake was the center of operations for two units of the 592d. The southern part of Laguna de Bay was under the control of General Griswold's XIV Corps. After attempts to clean out the Japs from the shores and islands of the lake proved difficult by land, the 592d were called upon to supply an "inland Navy." Pontoon bridges across the Pasig River prevented the entrance of even small boats, so the LCVPs chosen for the operation had to be taken overland on huge trailers and launched in the lake. 1st Lieutenant James Amory of Hilton, Virginia had six LCVPs operating under XIV Corps while 1st Lieutenant Albert Gappelli of Providence, Rhode Island, had four LCVPs in operation under General Swift's XI Corps. Both detachments did invaluable work running patrols and combat missions to various points around the shores and on the islands of Laguna de Bay.

In March of 1945 a task group was organized to move to Batangas on Southern Luzon to help establish a new base. This group consisted of Company C that was at Nasugbu and Company E that was stationed at Subic Bay. The task group was under the command of Major Rex K. Shaul. Company E with Major Shaul left Rifle-range Beach and proceeded to Nasugbu where they rested for a few days prior to moving on to Batangas. When the whole group finally arrived at their destination, work was started once again. The Boat Company provided lighterage and ran some combat missions while the shore company constructed roads and supply dumps. 1st Lieutenant John Kentzel of San Francisco, California, earned undying fame at Batangas in his position as labor king and mayor of the town.

By the middle of May most of the 592d Regiment had moved to the city of Batangas-that "garden spot of the Philippines." Major Frank L. Mann had left the regiment for assignment to the Amphibious Training Command and his Subic Bay detachment of Companies A and F were once more back in the regimental fold. Colonel Keyes returned to the United States for a well-deserved rest and Lt Colonel Kaplan assumed command of the regiment. For the first time in more than two years it looked as though the regiment was in for a relatively long spell of inactivity, so Colonel Kaplan made an all-out effort to make living conditions as pleasant as possible. In preparation for the rainy season all tents were given bamboo floors and frames, while drainage ditches and duck walks were laid throughout the area. Clubs were constructed for both officers and enlisted men. Dances, movies. And occasional USO shows provided them with adequate entertainment.

But even during this period of relative ease the 592d was not completely out of action, because part of Company B was still conducting missions along the southern shore of Luzon between Batangas and Legaspi. They had a detachment at Guinayangan and from there made the first landing at Pasacao after which re-supply missions were run between the two places. This detachment moved back to Legaspi, but on the 15th of May moved again from Legaspi to Mauban. After the fall of Manila portions of the Japanese Army fighting there with a particularly large number of "attached" personnel including Formosan and Korean slave laborers, retreated in a more or less orderly fashion south and east into the mountains and rougher country which offered better protection. Since there were no overland roads, the best approach to these Jap remnants was by sea. This was a made-to order job for the Amphibians. Part of Company B with their CMS and a rocket boat were sent from Legaspi to perform it.

The Japanese forces were holed up in the barren mountains south of Dilvgalen Bay and were a mixture of jap regulars with some Jap civilian workers and a great many Formosan and Korean "slave" laborers. Our LCMs worked as far north as Infanta, 300 miles up from Legaspi.

There was good evidence that the non-military part of the enemy population wanted to surrender but were held back by the military command. The 592d found itself engaged for the first time in a new type of warfare - psychological. This consisted of the installation of a high volume loudspeaker on the side of an LCM which was to cruise up and down the coast for a distance of about forty miles, going just as close to shore as they safely could. From the barge an American Neisi interpreter talked to the surrounded Japs. He urged them to surrender and explained just how it could be accomplished. This novel idea could not be considered a tremendous success for only a few women succumbed to the wiles of the loudspeaker. In dealing with the Japs it seems that bullets speak louder than words.

With the completion of their fifteen combat landings and the retreat of the japs into the hills, the 592d's job on Luzon was finished. What they had set out to accomplish was done. Corregidor had been recaptured and Manila was once again under American control. But the war was not yet over. Ahead of the American Army lay their one last objective on the road to Tokyo - the Imperial City itself.

Until that invasion would take place, the 592d EBSR, Brigade Headquarters, and the 287th Signal Company waited on Luzon; the 532d EBSR on Panay; the 542d EBSR on Cebu; and still on Leyte the remaining elements of the brigade including the Quartermaster Headquarters and Headquarters Company, the 162d Ordnance Maintenance Company, the 262d Medical Battalion, and the 562d Engineer Boat Maintenance Battalion. Everyone wondered what would happen next.

|