Chapter V

Salamaua, Lae, and Finschafen

EARLY in August a combat team composed of Companies C and D, E542d EBSR, under the command of Major (now Lt. Col.) Philip W. Long of Richmond, Virginia, relieved the Nassau Bay detachment of the 532d,EBSR. By then the 41st Infantry Division had advanced along the coast as far as Tambu Bay, four miles below Salamaua, and it was the 542d's job to keep them supplied and assist them in every way possible in their final dash on Salamaua. This promised to be no easy job, for the japs had received reinforcements from the north and were prepared to put up a strong resistance to any attack on their positions.

The combat team ran its first missions from Morobe to Nassau and from Nassau to the various beaches in the Tambu area. On the very night that they relieved the 532d EBSR detachment at Tambu they were subjected to continuous counter-fire of Japanese machine gun, mortar and artillery as the Yank infantry advanced to seize Roosevelt Ridge directly behind the bay. However, the unloading was not interrupted for the attitude of the shore party was that if the boat crews had guts enough to stick around and be unloaded under fire, they would unload them; while the boat crews announced that if the shore party had the stuff to unload them, they would put the boats on the beach. Fortunately, there were no casualties and by morning the new team had shown its mettle to the infantry who were convinced that here was another amphibian combination equal to any task placed before it.

The following week was one of greatly increased boat activity. Almost every night the boats ran two missions apiece carrying over 150 tons of equipment and personnel to the seven beaches north of Nassau Bay. During the day the same boats performed a variety of missions. The crew of the "Hector," a 542d navigation boat, under the command of Captain Wallace M. Mulliken of Champaign, Illinois, was often called upon to make a quick trip to the scene of a downed A-20 or B-25 to rescue the crew, or else to cruise slowly up and down in front of enemy positions to draw fire. Fortunately, jap artillery was poor and the "Hector" never received a direct hit, but the boatmen were always glad when a trip of that sort was over and Yank artillery opened up on the disclosed jap positions.

With the exception of a single night in the next two months, the Tambu Bay detachment received nightly fire from Japanese mortar and artillery. One night a dud fell six feet from their radio station. Whenever the shelling started, the boats waiting in the bay dispersed over a wide area, but those already on the beach being unloaded had to remain there. The spirit the men had displayed on their first night at Tambu never, slackened and work continued "as usual" during every enemy barrage.

Another night, the latter part of August, the Amphibs were not so fortunate. As ODO of the LCVs was being unloaded on Lovell Beach near Tambu during a heavy barrage it received a direct hit by a jap mortar shell. A three-foot hole opened in the port bow near the water line and the ramp cable was severed. Private First Class Pete Zubieta, Jr. of Elko, Nevada, seaman of the barge, was killed instantly along with several Australians in the unloading crew, The 542d coxswain, Technician Fourth Grade Leo Kordick of Bridgewater, Iowa, was wounded by shell fragments in the left hand, leg, and foot. Many others were injured along the beach or nearly buried under the shower of flying debris. Although the barge was apparently hopelessly crippled, Technical Sergeant (now 2d Lt.) Eric Hell Helleskov of San Francisco, California, and Technician Fifth Grade Joe Angerer of Grand Mound, Iowa, stuffed life preservers into the gaping hole and, after managing to raise the ramp despite the severed cable, retracted the boat and ran it twelve miles back to the base at Nassau Bay. This trip was fraught with tension and anxiety lest a wave should come crashing over the gunwales or push in their temporary life-preserver plug and sink the boat. They inched cautiously along until they finally reached home where the boat was repaired and soon placed back in service. For their gallant and courageous action both men were awarded the Silver Star. Landing craft were so scarce at that time that their, saving of this boat was especially valuable. The nearest replacement was a thousand miles away as Cairns.

After a few weeks American air power became superior enough to permit daylight runs, Running in the daylight hours resulted in easier boat control and quicker unloading by the shore parties. Over two hours were cut in the running of a mission from Nassau to Tambu and return. The boatmen also preferred the risk of Jap air attack because at nighttime any shell passing overhead sounds close but during the daytime the boat and shore personnel could observe shell patterns on the ground and water and proceed uninterrupted with their duties while areas 400 to 800 yards away were being shelled. Of course, the boat movements could be observed by the enemy and they were often harassed by shelling and air attacks, but they were willing to take that chance to get the job done. The detachment lost its first LCV one night toward the end of August. It was loaded with three tons of pierced planking which takes a long time to unload as it is so heavy and bulky. The surf was high that night and, while the boat was being unloaded, it shipped a large amount of water. When the coxswain retracted from the beach the motor drowned out and the surf caused the boat to broach, smashing her port stern against the starboard stern corner of an unloading LCM. The boat sank within five minutes. It was, as someone later remarked, “just one of those things.”

Early in the morning of 11 September a special reconnaissance mission was run with the object of discovering the extent of Japanese withdrawals and to spot the enemy’s gun positions around Salamaua, The boats were run at 500 RPMs with their underwater exhausts which enabled them to go under cover of darkness to within 100 yards of enemy lines. When dawn broke, the observers in enemy gun emplacements in Salamaua took the bait that was dangled before them and opened fire. Fire was returned by the little 30-caliber machine guns on the LCVs to keep the enemy distracted while yank artillery spotted their targets, aimed and fired. Because of this mission the infantry was able to move forward rapidly and by nightfall Salamaua was occupied by American and Australian troops.

The fall of Salamaua came 74 days after the assault on Nassau Bay. During this. period additional boats were brought up from Australia and put into operation by the Amphibs until they were running more than 100 barges. Their craft had made more than 300 tactical landings, transported nearly 10,000 troops, and carried over 15,000 tons of cargo. The effectiveness of amphibian warfare against the Japs had been proven. Meanwhile, the 532d detachment that had been relieved at Nassau Bay moved to Milne Bay to participate in some final maneuvers with the 9th Australian Division in preparation for the assault on Lae. Since early spring General Heavey had been planning the part the 2d ESB would play in this operation. It was decided that since the 532d EBSR had trained with the 9th Australian Division in amphibious tactics while at Cairns, they should also put these troops ashore at Lae.

The first step was to consolidate the already far-flung 532d regiment at their advanced base at Morobe. Authority was obtained to send the regiment from Cairns to that base where it would be joined by their several small detachments already located near there. Early in August they loaded on transports at Cairns.. Then the inevitable happened, new orders were received! A final dress rehearsal for the Lae assault would be held two weeks hence on Normanby Island in the Milne Bay area to iron out any difficulties that might possibly arise during the invasion. This particular site for the maneuver was selected because the Navy and Australian troops were stationed in that vicinity. But what a situation for the 532d! Most of the regiment were already loaded aboard transports and enroute to Morobe and the remainder were scattered in small detachments along the New Guinea coast from Oro Bay to Tambu Bay. To further complicate the matter, D-Day for the Lae operation had been tentatively set for September fourth which meant that the troops would have to be taken off the transports at Milne Bay while the men in the separate detachments were being relieved by another Amphib unit and were moving down to their base, then they would have to set up camp, participate in the rehearsal, embark again for Morobe, and complete their final preparations for the operation in less than thirty days! However, the Amphibs met this schedule in characteristic fashion. The rehearsal went off as planned and was generally considered to be very satisfactory. The principal point demonstrated by the rehearsal was that the Aussies were taking far too many vehicles in the initial landing. Loading plans were promptly corrected.

Immediately following the rehearsal the 532d was transported to Morobe in naval craft and upon arrival began rushing their final preparation. Final orders were received. The operation was to be a three-pronged offensive with a waterborne force landing east of Lae, a paratroop force landing northwest of that base, and an infantry force pushing up from the south. All three forces were to converge on the objective and annihilate any opposition. A large task force was assembled for the amphibious phase of this operation since the Japs were reported to have concentrated as many as 20,000 of their best troops at Lae, In addition to the LCVs and LCMs of the 532d, which were over 65 in number and carried personnel, tractors, beach matting to keep heavy equipment from bogging down in the sand during the unloading, conveyors for unloading heavy cases, vehicles, signal equipment, guns and ammunition, rations and various other essential supplies, the Navy was to furnish a number of their large landing craft and tank lighters. Major (now Lt. Col.) Charles B. Claypool, Hq. 532d, of Grand Rapids, Iowa, remained at Milne Bay to work out final details with the 9th Australian “Divvy” and the Navy. The Navy requested that the 2d ESB provide Amphibian scouts to go in on the first wave to establish markers on both Red and Yellow beaches and to make a beach reconnaissance. Major Howard Lea, the Brigade Operations Officer, arranged the scout detail which he ultimately led in the attack. Capt. (now Lt. Col.) Edward T. Rigney, Brigade Signal Officer, of Holliston, Massachusetts, prepared details of the final signal plan. Colonel J. J. F. Steiner, 532d Regimental Commander, of Birmingham, Alabama, was responsible for the regimental preparations and the execution of their part in the assault, although his Executive Officer, Lt. Col. Edwin D. Brockett of Fort Worth, Texas, would land with the regiment and direct their movements on the far shore.

Lae, New Guinea. 16 Sep 1943. View of Red Beach on D-Day as

532 EBSR lands 9th Australian Division. Shore Party unloading LCTs.

Plans for their part in the assault worked out to the last detail, Colonel Steiner saw to it that every last man in his regiment who would participate in the operation was well informed of the plan of action, what to expect, and exactly what he was to do. Sand table models of the beachhead were constructed and the operations were explained fully. Each man was made to feel that he would perform an integral part in what was to take place. They rested one day. Colonel Steiner felt that the preparation and training of his troops had reached a peak and that, like a highly trained football team, they should relax the day before the game. It was good strategy.

On that same day an incident occurred at Morobe that gave rise to some consternation and fear in the minds of many individuals about the probable outcome of all their detailed planning. General Heavey and several of his staff officers had arrived at Morobe to join Colonel Steiner and members of the 9th Divvy's staff for a last-minute conference after which they would all depart in the convoy to the far shore. While they were at their noonday lunch, a red alert was sounded but the all clear signal was given within ten minutes and the alert was forgotten. Soon the sound of planes was heard overhead but, as no alert was sounded again, they proceeded with-lunch thinking the planes were friendly. Suddenly the harbor was filled with the sound of exploding bombs and it was realized belatedly that the planes were Japanese. There was no damage and no casualties, but the question in everybody's mind was, "What do the Japs know?" Certainly they couldn't have missed seeing the LSTS, LCTs and other landing craft that were in the harbor.

Regardless of what the Japs knew or expected, the die had been cast and early that evening General Heavey and the other officers boarded one of the small naval APCs and within an hour the convoy got underway. As the convoy cleared the harbor at Morobe at dusk, a flight of P-47s were seen circling overhead and everyone agreed that it was a very comforting sight. Two hours after dark the 532d landing craft, proceeding under their own power over the 75-mile course across the Huon Gulf, joined the convoy off Kakari Point. So far everything was running precisely on schedule. The assault on Lae was at hand.

The landing at daylight the next morning, 4 September 1943, went off with the precision of a well-oiled machine. As the first faint streak of dawn crept over the eastern sky, the barge and small ships of the invasion force began moving toward the beach behind which could be seen a range of mountains towering 10,000 feet into the clouds. Inshore a long line of warships moved from the east into a position on each side of the beach chosen for the landing. As they did so, the jap shore batteries opened surprise fire. Their punishment came like a stroke of greased lightning. All the warships opened on them and their feeble protests at this unbelievable assault ended almost before it started. Spouts of white and yellow water spurted upward as the ships shelled the beach with increasing fury. The mist was split with flashes as tracer shells arching from gun to shore made orange-colored streaks against the dark background. For half an hour the bombardment thudded and clouds of smoke reeling upward announced that direct hits on enemy installations had been scored.

Then it stopped as suddenly as it had started. Through the dull, grey smoke and churning surf especially trained Amphibian scouts of the 2d ESB, dressed in Aussie uniforms, were first ashore to make a quick reconnaissance of the beach, ascertain enemy positions, .and guide in the landing craft. They signaled back that enemy opposition was negligible, and that most of the japs had either been killed in the bombardment or had fled to the safety of the hills behind the beach. By that time the Australian infantry were already clambering aboard the landing craft that waited patiently alongside the transport. Each man clutching his rifle in hands cold with sweat and uttering under his breath something that sounded like "Here goes nothing" or "This it it," cramped himself amid other green clad, tense, and eager infantrymen in the barge. Filled to capacity the barge quickly moved away from the ship to let another one in and headed toward the line of departure. As wave after wave of landing craft was formed, they shot forward on signal from their wave leader. Soon they were only fifty yards offshore, then fortv, thirtv, twenty, ten. Coxswains yelled, "Hold on! Prepare to land!" With a thud the boats struck sand, and ramps dropped and forty men from each barge jumped across the surf and were into the jungle in less than a minute.

Aussies unloading at Scarlet Beach from our LCVPs.

The shore engineers quickly organized the job of unloading supplies and getting them distributed over hastily-constructed roadways to their proper dump sites. Beach defenses were set up. The first barges unloaded tractors and big road graders and heaps of wire mesh that would be used to make passable roads over the sand and swamps. Working with power driven saws, the engineers felled thick palm trees which the tractors dragged to creeks or swampy spots. Bridges grew in minutes and, almost before the last log was in place, a "cat" crawled over and pressed farther with their road building. Within twenty minutes three roads had been gouged through the swamps to dispersal areas. The men worked like mad and unfolding the 10-foot wide metal strips and laying them over the beach sand. And still the barges kept coming! As soon as a ramp dropped on the beach a steady stream of soldiers seemed to materialize out of nowhere and, entering the barge on the port bow, they emerged on the starboard side a second later bearing crates and boxes, dragging guns and pushing heavier equipment. Sweating and swearing profusely, the Aussies and Yanks worked side by side in orderly confusion moving the cargo. As the Aussies later put it, everyone worked "flat out."

Most of the barges, relieved of their cargo, immediately retracted from the beach and headed back to their base at Morobe for additional supplies. About twenty, however, remained on the beach for use in emergencies and for "end runs" up and down the beach. 'The careful training and detailed preparations paid off well. The initial assault through unfamiliar waters, studded with coral reefs and "niggerheads," had been made in enemy territory successful and without loss or disablement of a single craft.

As a climax to this demonstration of American genius for rapid work with heavy engines, came the landing of the large LSTS. As these ponderous hulks drove to the beach even the longshoremen working frantically in their unloading of the smaller craft stopped to view these monsters as they magically opened their bows and dropped immense ramps slowly to the edge of the surf. It is impossible to enumerate the contents of one of these ships. Ton after ton of equipment was unloaded and, interspersed with the vehicles and material, companies of infantry filed out while artillerymen rode guns drawn by tractors. Here was the power with which the invaders could drive deeper and deeper into the enemy's defenses.

Shortly after seven o'clock, before the LSTs reached the beach, all bell broke loose. ,Jap bombers and Zeroes coming in just ;above the tree tops attacked in strength, the first of numerous raids of such proportion to come. Two of the large Navy infantry landing craft still on the beach were hit and disabled. The Amphibs, under prior instructions issued by General Heavey, had dispersed their small barges well offshore where they presented small targets for air attacks. It was the beach installations, including more than a thousand shore engineers of the 2d ESB, which bore the brunt of the enemy bombing and strafing. In this and subsequent jap raids, which continued at intervals day and night during the twelve-day battle for Lae, supply, fuel, and ammunition dumps were lost, the Amphib's regimental command post was nearly blown off the map when bracketed by four 500-pound bombs and direct hits struck the medical detachment area where wounded were being attended.

But the Navy continued to bring in supply ships and the shore engineers somehow managed to get them unloaded even though heavy rains had added to the difficulties ashore by turning the low terrain along the beach into a sea of mud and the dump areas into quagmires. Life on Red Beach during this period was most unpleasant. Death was frequent.

Meanwhile, the Aussie infantry was pushing southwestward toward Lae. Shore roads were impassible and the Amphibs kept their advance supplied by boat transporting troops, guns, ammunition, supplies and equipment down the coast from Red Beach to wherever they were needed. To meet the increased demand for boats it was necessary to increase the number of LCMs to 21 and to bring to as many as 60 LCVPs from Morobe. Every night the convoys of landing craft would feel their way through the uncharted coral to find a small strange beach on which to deliver their cargo. These boatmen were often under artillery and mortar fire as the Japs attempted to prevent this gradual encroachment of their coast.

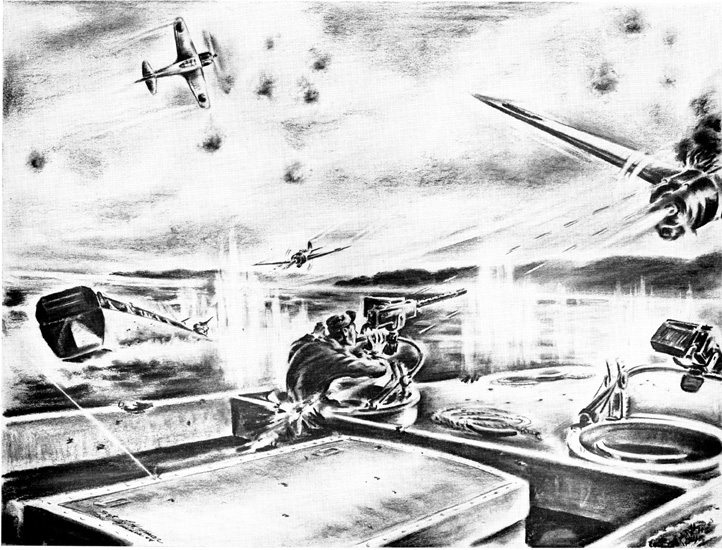

Strafed at Lae. T/5 Richard Kump, Company B, 532nd, killed by the Zero’s 20 mm after he had hit and set

afire the Jap with his .30. The Zero crashed. Drawing by Sgt L N Homar.

One night six of the anchored LCMs dragged anchors in a sudden heavy storm and, despite efforts to get engines started and take to sea, they were washed high up on the coral beach. The salvage detail was quickly called and through their earnest and strenuous efforts, every boat was soon refloated and put back into operation. Too little praise has been given the salvage crews for their quick thinking and quick action in emergencies similar to this one.

This same storm caught the Aussies attempting to cross the flooded Busu River. One battalion, by a combination of swimming and rubber boats, had managed to cross most of its personnel and get a foothold on the other side. During the crossing many of the men had lost their rifles and not one machine gun had been transported over the river. Here was a critical situation. The Japs held the coast just west of the river mouth and probably realized that only a small and poorly armed force had succeeded in crossing the river, which was still rising. Would the Japs attack? 1st Lt. (now Capt.) Henderson E. McPherson, 532d, of Sharon, Pennsylvania, and his boat crew volunteered to attempt ferrying the remaining troops around the river mouth. The infantry commander, considering the losses his force had already suffered due to enemy fire and drownings, was reluctant to risk more casualties in the hazardous crossing until the Jap defenses could be softened up, but, nevertheless, he agreed. For forty-eight hours the 36-foot LCV shuttled fresh troops to the beleaguered beach and brought back the wounded under a continuous barrage from Jap machine gun, mortar and artillery fire. When the rudder was shot away, they improvised another and Lt. McPherson sat in the stern fully exposed to enemy fire and steered the craft. This two-day nightmare ended only after all the twelve hundred troops and a great quantity of supplies had been successfully landed on the west bank of the Busu. They had made a total of forty trips. For his outstanding heroism beyond the call of duty, Lt. McPherson was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and his four crew members, Sgt. Albert Holtslaw of Sandoval, Illinois, Sgt. Ernest R. Hammond of Maguan, Illinois, Cpl. Paul F. Radeski of Waldo, Wisconsin, and Private First Class George W. Winger of Soldier's Grove, Wisconsin, each received the Silver Star.

Amphibian engineer machine gunners both on the boats and ashore were often able to bring down jap planes with their 30 and 50-caliber fire. Usually there are so many guns pouring lead at the attacking planes that it is almost impossible to tell who scored the hits but during the Lae operation the 532d EBSR shore engineers were credited with definitely shooting down two Jap planes. The boat engineers, not to be outdone shot down another two planes from their boats. The Japs pilots must have figured that these small craft were defenseless and an easy target for a strafing attack, for it was under just such circumstances that Private Richard Kump, Co B 532d, of Brooklyn, New York, died a hero but not until he had gotten his Zero. Private Kump was manning a machine gun on a landing barge ferrying troops to a forward beach when a Jap plane appeared overhead. One Zero singled out the small craft for attack and zoomed down, his guns spitting death, But Private Kump stuck to his gun and sent the jap blazing into the sea. At almost the same instant he was struck by a 20 mm shell from the Zero. Due to his heroic action the boat and its other occupants reached their destination safety, and, for the gallantry that he had displayed in the face of intense enemy fire, Private Kump was awarded the Silver Star posthumously.

Brigade boats continued to work with the Aussies plying up and down the coast until Lae finally fell on 16 September. During the twelve-day campaign and the subsequent assembly of troops in and near Lae, lasting until 30 September, the relatively small force of boats had transported over 10,000 tons of cargo and 12,000 troops. But this was not done without its expense in men and equipment. The 532d reported nine men killed in action, five officers and sixty-one men wounded in action, and five landing craft damaged beyond repair. Major General Wooten, the Australian Commander, stated: "Not for one hour has my advance on Lac been held up by failure of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade to deliver troops, supplies or ammunitions at the time and place needed."

From a military standpoint the operation was a complete success. The loss in lives and equipment was kept at a minimum and was only a fraction of the losses sustained by the enemy. This is in itself unique for usually in amphibious warfare the troops on the offensive figure on suffering much heavier initial losses than the defenders. With the fall of Lae another great step had been taken, to drive the jap from their bases on New Guinea.

Then came the assault on Finschhafen which was pretty much the story of Lae all over again. General MacArthur, figuring that a quick amphibian strike at Finschhafen would catch the enemy off balance, ordered such an attack for 22 September 1943. With only four days preparation the landing was made on schedule; the Aussie 9th "Divvy," the 532d Amphibs, and the Navy working together again as they did at Lae. A short naval bombardment preceded the dawn assault made on Scarlet Beach, a few miles north of Finschhafen village on the tip of the Huon Peninsula. While this was in progress our Amphibian scouts were already on their way toward shore and, as soon as the barrage lifted, they hit the beach. The going was not easy for the Japs had lined the beach, with strong and well-camouflaged pillboxes, some of which had escaped destruction in the shelling. The scouts had to fight their way up the beach inch by inch. Their officer, Lt. Edward K. Hammer, 592d EBSR, of Franklin, Michigan, and Lt. Herman A. Koeln, 592d EBSR, of Brooklyn, New York, each killed Japs with their tommyguns. Despite this heavy opposition the scouts managed to set up range lights, flank markers, make a rapid survey of the beach and radio the result of their reconnaissance to the ships waiting offshore. The remaining waves came in according to schedule through a hail of enemy fire from the pillboxes. Some casualties were suffered but the boats were undamaged. Australian infantry swarmed up the beach from the barges and plunged inland to silence the jap batteries and snipers. The shore engineers immediately set up their beach defenses and assisted by Australian labor crews, pitched in to unload the naval craft. Everything on the beach ran smoothly. The road building progressed so rapidly that part of the time the engineers were working right in the midst of the front line infantry.

The day after the assault on Finschhafen, General Heavey received the following message from General MacArthur: "Mv heartiest commendation to you, your officers, and your men for their splendid performance in the Salamaua-Lae-Finschhafen operation. They showed skill, courage and determination."

One of the hardest worked and hardest hit units on the beachhead was the Amphib's Medical Detachment. Because of the heavy opposition encountered on the landing, their work began the moment they hit the beach. Due to constant ground action and frequent air attacks, it never ceased. The medical unit administered first aid, performed emergency operations, removed shell fragments, and dressed wounds. They worked tirelessly. In the midst of their heroic action on the second day after the landing a formation of twenty-seven jap bombers appeared overhead and, although the ack-ack gunners kept them at a high altitude, they succeeded in dropping their bombs on. the beach area before hastening away and before American fighters could catch them. Fortunately, the 532d had moved from its former area. It was turned into a shambles by the bombs. As it was, four daisy-cutters landed in their new camp area. One hit in the trees over the medics and fragments fell into the nearby foxholes. Capt. Charles F. Pecoraro of Stamford, Connecticut, and Capt. Frank J. DeCesare of Methuen, Connecticut, had both rushed for the same foxhole and Capt. Pecoraro, who was the last to arrive, was killed instantly. Capt. DeCesare received severe wounds on his left shoulder. One enlisted man, Tec. 5 Joseph H. Estes of Washington, D. C., was killed and three others were wounded. Several shore engineers rushed to lend their assistance to the badly-hit medics and it wasn't long before the detachment was reorganized and the job of treating other casualties went on.

Bombings continued every day for the next two weeks. Some raids were heavier than others but the men only dug their foxholes deeper and covered them with sandbag rooftops. They soon noticed that most of their raids came around meal time when they were lined up for chow, so a system of staggering the messline was worked out so that when a man got his food he would take it to a nearby foxhole to eat it. Some of the men were shaken up severely during these incessant raids and had to be evacuated but the majority remained calm and "took it as it came." Incessant and heavy raids and the monotony of "C" rations added to the difficulties. In those days there were not even the "10 in 1" rations to vary the food.

Meanwhile, the Aussies pushed south toward Finschhafen, encountering ever increasing Jap resistance. The Amphibs ashore had to assume most of the responsibility for the defense of Scarlet Beach, not only from the sea approach, but the beachhead perimeter as well. The boats continued to shuttle up and down the coast between Scarlet Beach and Lae, a distance of about seventy-five miles, to bring up supplies and evacuate wounded. The infantry was resupplied in their march on Finschhafen at the only intermediate point between Scarlet Beach and Finschhafen where boats could land - Launch Jetty. The rest of the shore-line was a mass of unbroken coral rocks and cliffs. This particular spot was not too good since it was too small to accommodate many boats but it was the only one available. It is interesting to note that a few months later Brigade Headquarters was established on a small point directly opposite this jetty.

Early in the evening of 2 October news was received in the 532d camp that the Aussies had entered Finschhafen. Their objective had been achieved but the operation was far from over for the Japs were still putting up stiff resistance in the mountains, especially, at Satelberg.

Twelve miles off Finschhafen lay the Tami Islands, suspected of being occupied by the Japs. Their location was suitable for radar and antiaircraft installations for the protection of the harbors in and near Finschhafen. Just before dawn on 3 October a force of 14 LCVPs and 2 LCMs carried a company of Aussie infantry through the encircling coral reef around the islands. Instead of the hot fire from Jap shore batteries that they had expected, natives in outrigger canoes joyfully greeted the white men. They explained in their pidgin English that the Japs had occupied their island "for many moons" and had left “only half a moon ago." The well-constructed pillboxes covering the only landing beach clearly indicated that an earlier landing would have met terrific resistance.

Back on Scarlet Beach heroism was the rule rather than the exception. The going there was tough, but the American soldiers - most of whom had been so recently mild-mannered civilians - were tougher. The exploit of Junior N. Van Noy, an Amphib from Preston, Idaho, was such that a grateful nation awarded him-posthumously-the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was the first engineer soldier in World War II and the first member of the Army Service Forces to win this highest possible award.

This tow-headed, red-cheeked kid was only 19 years old when he joined Co E 532d EBSR, back in Cairns, Australia. The fellows in the outfit didn't pay much attention to him. He was so mild mannered that his buddies considered him something of a mama's boy. Known as "Junior" or "Whitey", there wasn't a more unobtrusive individual in the company. But Van Noy soon showed them that no matter what they thought of him, he was a good soldier. He was assigned to the crew of a 50-caliber machine gun, and, proud of his job, worked hard to become a good gunner. During his first action on Red Beach, near Lae, he shot down a low-level jap bomber trying to strafe the beach and the barges. On D-Day at Scarlet Beach he wasn't so lucky for he received five shrapnel wounds in his wrist, side and back. The medics wanted to evacuate him but he steadfastly refused. They had another chance when he came to them a few days later with a severe case of ear ulcers, but again he refused. His company needed machine gunners and he meant to stay. Maybe it's of just such stuff that heroes are made. It seems so.

Van Noy and Poppa of 532 fight the Japs at Scarlet Beach.

Courtesy Look Magazine.

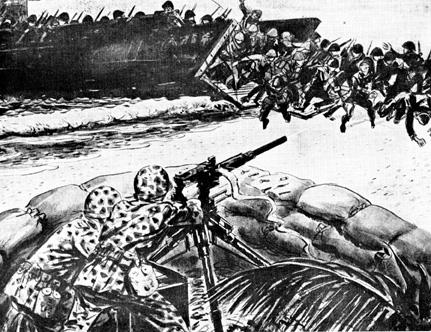

An hour before dawn on the stormy morning of 17 October 1943 Van Noy and the rest of his gun crew were trying to get a few winks of sleep in their hammocks strung between palm trees near their beach gun while Sgt. John Fuina of Brooklyn, New York, in charge of the beach detachment, remained on the alert to rouse the others if anything happened. Another member of the crew, Tec 5 Raymond J. Koch of Wabasha, Minnesota, was restless, and, unable to sleep, got up to take a stretch and smoke a cigarette. Gazing out into the sea the two men noticed four smudges on the skyline. Holding their breath, and clutching each other’s arms, they waited.

The smudges gradually took more distinct shapes as they moved toward the shore. They had the decidedly peaked prows of Japanese landing barges-and they were only 400 yards away. It hardly seemed possible, but there was no mistake. They were Japs! Later reports indicated that ten Jap barges had started out for this attack, but only four remained to charge the beach. Taking advantage of the dark night and rough sea, the jap boatmen let their ramps almost down when 600 yards offshore, cut their motors and were quietly paddling their boats in for the landing. Fortunately, Sgt. Fuina had spotted them. He yelled an alarm and ran toward his 37 mm antitank gun to fire an alert. Cpl. Koch ran from hammock to hammock to awaken all the gun crews, but Pvt. Van Noy, awakened by Sgt. Fuina's first yell, was already in his gun position. His loader, Cpl. Stephen Popa of Mayville, Michigan, was right after him. Their gun was only fifteen yards from the water's edge and, when some of the larger guns to their rear opened up, firing blindly, Van Noy held his fire. That took guts. The barges kept coming in, almost under the very nose of Van Noy's camouflaged gun. Then the japs started to hurl grenades by the handful, and one burst in Van Noy's gun emplacement. It was just a luckv toss for the Japs still couldn't see the gun position and Van Noy had held his fire, for that one reason. The shrapnel shattered one of Van Noy's legs and wounded Popa. It looked as if they had waited too long and lost. A sergeant back of Van Noy, seeing that they couldn't hope to hold out, shouted to them to get back from the beach. Aussie Bren gunners, between bursts, yelled, "Come out of there, you bloody fools." But the two gunners refused. The ramps of the jap barges fell to the beach and, when the invaders blew their bugles and began to charge, Van Noy pressed his finger on the trigger. His gun spat angrily and fatally. The first to fall were two jap officers trying to scorch the gunners out of their position with flame throwers. Behind them other japs flopped on the sand, firing and throwing grenades. Van Noy was seen to install a second chest on his gun and reopen fire with japs only a dozen feet away. His gun traced patterns among their forms as thev tried to crawl forward. One after another was hurled into eternity as his gun flashed. But in the darkness he couldn't hope to see all the japs edging toward him. His gun finally went silent, but only a handful of Japs had escaped that gun's fire. None of the other guns on the beach could fire on the particular spot where the Japs landed.

After it was all over they found Van Noy dead, his finger still on the trigger, the last round fired from his gun. Popa, alive but unconscious, lav with a dead jap sprawled across his body. Badly wounded, he had managed to grab a rifle and fire a bullet into the head of the jap coming at him with a bayonet. Van Noy and Popa, who was awarded the Silver Star, virtually had defeated the landing attempt with their one machine gun. The Japs didn't try another landing on Scarlet Beach.

About a year later the Army Service Forces in Washington, D. C., developed a new type of port repair ship, a seagoing vessel of 2500 tons. When the first one was launched, it was christened the "Junior Van Noy" in honor of the 19-year old American boy who gave his all for his country on battle-scarred Scarlet Beach in New Guinea, far from his beloved Idaho.

A large part of the brigade was concentrated in the Finschhafen area during November and December to continue amphibian support and supply to the Aussies as they pushed on north toward Sio. Other elements of the brigade were established on Palm Beach at Oro Bay as they arrived from Australia.

Stubborn jap resistance was encountered on Satelberg Ridge about 15 miles north of Finschhafen and for several days the Aussies unsuccessfully attempted frontal and flank attacks up its slopes. It was here on Satelberg that, for the first time in the Pacific theater, the Amphibs used the new 4.5" barrage rocket which, until then, had been held back as a secret weapon. This is the weapon the brigade had demonstrated to important officers in Australia in April, 1943.

Major Charles K. Lane of Severna Park, Maryland, later appointed Commanding Officer of the Brigade Support Battery, and Lt. Vermell A. Beck of Nephi,. Idaho mounted rocket launchers on a 3/4-ton weapons carrier. Aided by Sgt. Chandler Axtell of Johnson City, Tennessee, they succeeded in moving this carrier and the rockets several miles through the jungle and up a steep mountain to a point from where they could fire on Satelberg. They let loose with the rockets on the surprised Japs. Startled by this new type of weapon, jap artillery opened up in wild firing against this new enemy, but, as they could not tell from where the rockets were coming, their fire had no effect except to disclose their positions to Aussie artillery and to the Aussies Matilda tanks that were climbing up the slope. The roar of the exploding rockets drowned the noise of the advancing tanks which went on to blast out pillboxes and capture the ridge. In addition to the Japs who were killed by the fragments from the rocket projectiles, others were found dead without a scratch on them--victims of the terrific concussion of their explosives.

After the capture of Satelberg on 26 November, the Aussie 9th Division continued their drive northward to Sio with the Amphibs serving as their "Navy." The coast from Finschhafen to Sio was much different from that previously encountered. Here were very few beaches and those spots that could be called beaches were small and often very rocky. Between these few beaches were shores as rough and rocky as the "rock-bound coast of Maine." Once around the Huon Peninsula the boatmen found seas much rougher in the tide rips of Vitiaz Straits, but, always eager to meet new difficulties, they tackled their new situation with their characteristic determination. Occasionally jap planes dared to strafe our boats, but it was not like the early days. American planes were beginning to do their stuff and chased the japs out of the skies. On 17 January 1944, Sio was occupied and the Huon Peninsula was again in the hands of the Allies.

The relations between the Amphibs, the 532d EBSR in particular, and the 9th Australian "Divvy" were at an end. The successful campaigns of Lae and Finschhafen could never had been accomplished without the closest cooperation between the staff officers and both organizations, and the close comradeship between the, Aussies and the Amphibs. This. cooperation and comradeship was commended in an article that appeared in an Australian newspaper:

"The Lae and Finschhafen campaigns have provided a fine example of the effectiveness of Australian-American cooperation. In addition, the A.1.F. has been supplied by its 'Navy,' a fleet of barges manned by the 2d Engineer Special Brigade. Cooperation in the air is an impersonal detached matter. In an entirely different category is the active man-to-man cooperation of the U. S. boys who man the supply barges. These Yanks have fought and some have died alongside Australians and have done both so gamely as to win the respect and affection of the Diggers.”

Information was later received by Lt. Col. Brockett that several members of the 9th "Divvy" had petitioned their army commanders to grant permission to the 532d Engineers to wear their famed "T" which they had earned for their gallant defense of Tobruk in North Africa two years previously. . Although nothing official was ever received, the 532d appreciated this very noble gesture on the part of the' Aussies. For his meritorious service rendered in the direction and coordination of work of the 532d EBSR on the far-shore during these two campaigns the Australian Government bestowed on Lt. Col. Brockett the, Distinguished Service Order, the British equivalent of our Distinguished Service Cross. In accepting this award Colonel Brockett extended his gratitude and explained that it was not through his efforts alone but the cooperative efforts of every man in his regiment that had brought them success in their Lae and Finschhafen operations.

|