Chapter VI

New Britain, Saidor, and the Admiralties

BEFORE jumping immediately from the landings on the Huon Peninsula to those in in the Bismarck Archipelago, let us go back a bit and see what the other brigade units were doing in the meantime.

By the end of October, 1943, all units of the brigade had moved from Australia to New Guinea. With the exception of the 532d regiment and the combat team of the 542d that were engaged in the Salamaua-Lae-Finschhafen operation, they had established their camps in the vicinity of Oro Bay. Most of them were on a nice sandy beach appropriately called Palm Beach. The 562d Boat Maintenance Battalion was set up right in the harbor. The nightly air attacks on that base were just about over, although those who had not previously made the acquaintance of "washing machine Charlie," the common appellation given to a lone nuisance jap raider, still had an opportunity to do so now and then. Alerts were frequent.

One morning about the middle of October the members of the Oro Bay units had ringside seats at an air show that they would never in their lives hope to see again. It was the Jap's last big effort to attack Oro Bay, but for them it was death in the air. An alert had been sounded and, as was the custom, the men ran to the beaches or high knolls to get a better view of the Jap attackers rather than to foxholes where they would be safer. High overhead they could faintly see wave after wave of Jap bombers evidently coming to hurl destruction on the numerous ships in Oro Bay harbor. It looked bad. Suddenly, even higher than the Japs, and directly out of the sun, zoomed a squadron of American P-38's. The unsuspecting japs were caught by surprise. The men on the ground watched this scene at first with bated breaths. Then, with a sigh of relief, they burst into applause as one American fighter after another peeled off to attack the japs. Soon one jap burst into flames and plunged from high in the sky into the deep sea. Others followed in rapid succession. Fourteen Jap planes were counted destroyed before the remaining aircraft, still fighting, disappeared into the distance. The official communiqué of the next day stated that forty-six Jap planes had been definitely downed in the fight and not one of them returned to their home field.

"The loudest noise ever heard in New Guinea" occurred while the Amphibs were in Oro Bay and those who were in close proximity to the explosion will never forget it. The big bang occurred late one afternoon in October when a dump of bangalore torpedoes located just across the Palm Beach Road from the 592d Regimental Area was blown skyhigh. The cause was undetermined, although, sabotage was suspected. Some observers blamed it on spontaneous combustion. Fortunately, no one was hurt and, regardless of what set them off, that explosion was, to quote several Amphibs, "really something."

Some of the other things that will long be remembered by the Amphibs during their stay in Oro Bay were the soft-ball games on the parade ground, the USO shows with Gary Cooper, Phyllis Brooks, and John Wayne, the first furloughs to Sydney, the turkey dinners at Thanksgiving and Christmas, the unique bamboo chapels that the 542d and 592d regiments constructed on Palm Beach Road, the big sign near Oro Bay village that said "All Roads Lead to Tokyo" and, directly beside it, that long road with roller-coaster curves that led to Brigade Headquarters. The officers and men of that headquarters recall very vividly one noonday when the Aussie troops across the valley decided to do some practice firing. Something must have gone wrong because, all of a sudden, bullets were raining in the 2 ESB area. Being noonday some were naturally enjoying a siesta, but all thoughts of continuing such a pleasant pastime that day fled when they heard the bullets and saw little holes magically appear in their tent canvas. There was a quick mass exodus from the area. No one was hurt, but whenever the subject comes up in the course of conversation, as it often does, they say "you should have seen the officers scramble up that hill," and "I never saw 'him' move so far so fast."

Yes, there were some great times at Oro Bay, but there was also a lot of work. The boats were busy performing lighterage duties in the harbors at Oro Bay and nearby Harvey Bay; the 592d had a special boat detachment at Buna working mainly with the Australians. The Ordnance Company was busy experimenting with flak and rocket LCMs to be used in future landings and the Boat Maintenance Battalion was hard at work keeping all landing craft in a high state of repair. General Heavey insisted that everything possible be done to aid the troops in the forward areas and, as money and mail are prerequisites of high morale, the Brigade Finance Officer, Major George H. Flowers Jr. of Richmond, Virginia, and the Brigade Postal Officer, 1st Lt. Clifford F. Kluck of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, made several trips to those areas to pay the men and to straighten out the mail situation.

When our landing craft first arrived at Oro Bay in early June, 1.943, jap observation planes were frequently seen overhead. It was desired to conceal from them the fact that the Americans were accumulating at Oro Bay a large number of landing craft. Accordingly, these boats were hidden in two small streams which emptied into Harvey Bay three miles from Oro Bay where the heavy jungle growth completely hid these streams from spying japs. It was a weird life our boatmen led in their boats hidden away in these streams.

At first crocodiles were unwelcome neighbors but, when they realized the boats were there to stay, the crocs migrated somewhere else. Mosquitoes at times were bad but usually there was enough wind to blow them deeper into the jungle. On one occasion a group of generals from the South Pacific toured the boat anchorages up the two streams. They remarked that never had they seen such heavy jungle growth with the mass of roots of the mangrove trees and they marveled at how our boatmen adapted themselves to this strange life. There were no banks of the streams to which they could tie up the craft. Instead the mangrove swamps extended a hundred yards on each side of the narrow stream. Most of the men slept in their boats, but some constructed huts in the trees and lived like real tree dwellers.

The Chief of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold from Washington, D. C., accompanied by Major General Hugh J. Casey, Chief Engineer for General MacArthur, visited the brigade units at Oro Bay about the middle of November. They showed great interest in the Brigade's activities and of details of the landings at Nassau Bay, Lae, Salamaua and Finschafen. Shortly before their departure a review was held in their honor on the 2d ESB Parade Ground. This was the largest brigade review ever held in New Guinea, although several units in the brigade were absent at other stations. To many it recalled the big farewell review held at Fort Ord almost a year previous. Meanwhile, a plan for the invasion of New Britain with its Jap stronghold of Rabaul. was being prepared. Details were worked out at Goodenough where the Army had its headquarters. The 2d Brigade had a planning team there for several days. As long as the Japs controlled New Britain, which was only separated from the allied base at Finschhafen by the narrow Vitiaz and Dampier Straits, they could receive supplies from the north and thwart any allied advance up the northern New Guinea coast. General MacArthur contemplated the seizure of the western tip of the island and the control of these vital straits by first invading southern New Britain with an amphibious assault at Arawe and then making sweeping end runs to the north for landings on Cape Gloucester.

The 592d EBSR, which had not yet been engaged in actual conflict with the enemy, was chosen by General Heavey to be the 2d ESB unit to participate in the New Britain operations. The officers and men of the regiment received this news with joyful hearts for they had been anxious to get into the fight for a long time.

Colonel William N. Leaf, the 592d's Regimental Commander, of Staunton, Virginia, divided the personnel of his regiment into several different task groups, each of which would handle a separate operation. For the Arawe task group he placed Lt. Col. William A. White, his Executive Officer, of Memphis, Tennessee, in command and gave the task to Company B. The boats and crews of Company B, along with necessary clerical, boat maintenance, signal and medical personnel, moved to Milne Bay where maneuvers and rehearsal were held. D-Day for the operation was set for 15 December. Originally the assault had been scheduled for the first of December at Gasmata and with troops of the 32d Infantry Division, but that plan was dropped in favor of a smaller landing at Arawe with troops of the 112th Cavalry RCT.

Actually, the Arawe landing was a feint to deceive the japs as to the later more important landing to be made on Cape Gloucester on the northern coast. The Arawe force was to be the bait to attract the Japs while the larger force moved around to Cape Gloucester. Our men knew nothing of this. All they knew was that it was to be a hot landing right in the jap's backyard. As far as they were concerned their landing was the important one.

A full-scale demonstration was held on Goodenough Island early in December, our task group moving there from Milne Bay in its own craft. The results of that "dry run" were very encouraging. The cavalry and the Amphibs clicked. The next few days -were spent on minor boat repairs and other last-minute preparations. Two days prior to the assault the Amphibs loaded 16 LCVs and 2 LCMs on the transport "Westralia" while 1 LCM and 2 Rocket DUKWs were placed on the LSD "Carter Hall" along with the "buffaloes" attached to us for the landing. Meanwhile, an echelon of 8 LCVS, 13 LCMS, and a Halvorsen control boat was proceeding under its own power from Goodenough to Cape Cretin to join and LCT convoy to the operational area on D-Day. This was a rough trip in choppy seas, but all craft made it under their own power.

The actual assault was broken into four operations: a small surprise landing west of Cape Merkus, a full-scale attack on Cape Merkus, and two separate support landings on the islands of Pilelo and Arawe. The 592d boats participated in the main attack on Cape Merkus and in the support landing on Arawe Island.

The convoys arrived off Arawe well before dawn on 15 December 1943. So far everything had gone well and according to schedule. It was a moonlight night. Our hopes that the moon would be clouded over due to the rainy season were in vain. The surprise landing was attempted without a preliminary bombardment in order to gain surprise. Before the landing party reached the beach in their rubber boats, the Japs opened with a terrific crossfire and repulsed the assault with over fifty per cent casualties. One destroyer moved, in to shell the beach but this action came too late to save the situation. Now the Japs were on the alert and in all likelihood prepared to resist other landings that might be attempted on their shore before dawn. For the leaders of the task force there was plenty of cause for worry but there was no change of plans. The main assault on Cape Merkus opened at dawn, with a fifteen-minute bombardment of the beach by the warships and a strafing attack by a squadron of B-25's after which two brigade Rocket DUKWs under the command of lst Lt. (later Capt.) Walter D. Beaver of Kew Gardens, New York, laid a barrage on the beach to cover the assault waves of tracked landing vehicles. This was the first time in the Pacific area that rockets were used in a combat landing. Due to the wind and currents the buffalos and alligators had trouble in keeping a formation and failed to reach the beach on time and in the order planned. Meanwhile, the 592d craft were being formed and, as they were more powerful and could better cope with the winds and currents, they proceeded to the beach behind the alligators without difficulty. The beach itself presented another problem as it was far too narrow to accommodate a full wave of boats. Moreover, it was badly congested with these tracked vehicles. The LCVs and LCMs went in as far as possible, dropped their ramps, and the troops bad to wade ashore between the buffalos and alligators.

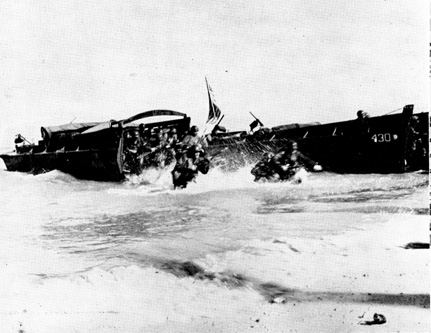

Arawe, New Britain. 15 December 1943.

Hitting the Beach in coral studded waters.

Despite many reefs, LCVPs of Co B, 592 EBSR

get infantry to beach in time to

accompany “Alligators” inland.

Infantrymen carrying supplies ashore.

The operation proceeded much slower than was anticipated but, fortunately, there was no opposition and all troops were landed safely. The naval bombardment and the rocket fire had been too much for the Japs. The Amphibs carried out the third phase of the operation by landing a force on Arawe Island without difficulty, After unloading troops and supplies they assembled off Pileto Island where another cavalry detachment had landed in rubber boats.

Everyone awaited the Jap air reaction for it was certain he would not allow this landing near his fortress of Rabaul without strong air attacks. Soon there was a Red Alert. Our covering fighters were seen to speed off to the north to meet the approaching japs. It was a Jap ruse that worked for, while our fighters were drawn off to the north, a second group of bombers came in on us from the east. Nineteen enemy aircraft bombed and strafed the beach and landing craft. Here was a real battle with Jap air power and our fighter planes were away. Bombs dropped all around the naval craft and our landing boats. All guns fired on the attackers and the 592d was officially credited with destroying one of them. Considering, the number of. bombs dropped we came off light; one LCVP was hit and three of our men were wounded. This was their first air attack and only a sample of the numerous and more intensive raids that were to follow. The training the boatmen had received in antiaircraft firing was most effective and before they left Arawe a couple of months later they had a total of five Jap planes to their credit. Their hot fire drove off many other attacking planes and probably damaged some of them.

The morning after the assault several reconnaissance missions were carried out along the coast and among the adjacent islands. To give added speed and still retain the maximum fire power on these missions, the two rocket DUKWs were each loaded on LCMS. They encountered no opposition on their first missions and it was believed that whatever japs may have been in the vicinity to resist the first surprise landing had either been wiped out or had fled to inland installations. That was later proved to be an erroneous assumption for many japs still remained only a short distance away to continually plague the allied advance.

On the second day Arawe was again heavily bombed and several small naval ships in the harbor were severely damaged. Our commander, Lt. Col. White, had the misfortune to be on one of the Naval patrol vessels when it was struck with a direct hit. With bombs and strafing fire raining all around them, the Amphibs went to the rescue in their small boats. They succeeded in saving all personnel of the ship, which sank in four minutes. Lt. Col. White suffering from multiple leg fractures, was pulled from the water in the nick of time. He was immediately evacuated and Major (later Lt. Col.) Cecil R. Bilger, his Executive Officer, assumed command of the task group. Lt. Col. White was later returned to the United States where he recovered from his wounds and participated in many War Bond rallies at various large defense plants.

At Arawe the Amphibs also had their first "naval" engagement with the jap barges. Intelligence reports had been received stating that there were no jap barges within a range of fifty miles, but the Task Force Commander desired a. reconnaissance - made to be certain he would not be counter-attacked from the sea by barges hidden behind some of the numerous islands near there. A two-boat patrol under the command of Lt. Edward C. Coleman of Brockton, Massachusetts, went out searching among the islands in waters too shallow for the PT boats but just deep enough for LCVs. It was not long before contact was made. Jap barges were hidden only four miles from our base! Early the next morning the two rocket DUKWs were loaded on LCMs again and, with a third LCM for escort, they went to the area where the jap barges were located. A concentration of 180 rounds of rocket ammunition were fired into the area and everyone of the eight barges concentrated there was sunk. The Task Force Commander had also ordered them to destroy the native village of Mielelek, which was only 500 yards farther along the beach, because it had been reported by the natives that the village contained large stores of jap food and ammunition. An additional sixty rounds were fired into the village and, when the Amphibs left, it was completely destroyed. Their report to the Commander consisted of just two words: "Mission Accomplished."

In their next "naval" engagement the 592d boatmen were not so lucky. 2d Lt. (later 1st Lt.) David D. Williams of Grosse Pointe, Michigan, was in command of two LCVs carrying five cavalrymen, two Australian ANGAU representatives, ten men from the 592d detachment including himself and a medical aid man, and five native police boys. Their mission was to proceed eighteen miles up the coast to the mouth of the Itni River where all but the 592d boatmen were to be put ashore to reconnoiter and determine the jap strength in that vicinity. It, was thought that the trip would take five to seven days, so a sufficient stock of supplies was loaded on the boats.

The party left early in the evening on 17 December and planned to go as far as Cape Peiho where they could pass the remainder of the night in a small lagoon and continue on from there in the morning. This would enable them to reach their destination during the daylight hours. When they reached the lagoon they found it to be far too shallow so, on the advice of a native guide who was supposed to know the area thoroughly, they headed toward a mangrove swamp in Margie Bay just south of Cape Peiho. This wasn't much better since they had to slowly cross a barrier reef to enter the bay. Furthermore, they couldn't get near enough to the shore to have the camouflage protection of the giant mangroves. They were still in an exposed position, but, as it was dark in the shadows of the shoreline, they decided to risk it for the night and to get out as soon after dawn as possible. Unfortunately, when dawn broke and they were preparing to leave, they saw a jap barge moving about 1000 yards offshore. The japs on the alert also discovered them. Soon six additional jap barges appeared and deployed to cover the pass from the bay. The first reaction of the Amphibs, not knowing the armament of the enemy, was to put up a bold front and make a dash to the open sea. This they tried, but again the native guide gave a faulty direction, and one of the Vs ran on the coral reef. It took some time and plenty of courage for the men in the other boat to pull them off. Then they realized that the first V was too badly damaged to even attempt a long trip on the open sea, particularly at full speed. Meanwhile, the Japs were closing in rapidly and soon opened fire. The Amphibs returned the fire with their four 30-caliber machine guns and a few rifles. Our tracers were seen to hit their boats but the Jap fire, while not too accurate, was overwhelming. Lt. Williams ordered the boats back into the bay where he felt his men might possibly get ashore and obtain refuge in the jungle. Just as they beached the japs got the range with a 20-mm gun and wounded four men, including one of the boatmen, T/4 Robert F. Winter of Wilmette, Illinois, who was shot three times in the left leg and twice in the right. The boats were abandoned immediately and the men waded ashore in the waist-deep mud carrying their wounded and two of the machine guns with them. The Japs were reluctant to go ashore, apparently fearing our fire. This was a break for the Yanks. However, they were still in a most difficult position for, after the japs left, they inspected their boats and found them damaged beyond repair. To return to their base at Arawe they had only one alternative - to take an overland route through the jungle. Supplies and the backplates of the machine guns were removed from the barges which were then sunk in different places in the swamp. The medical aid man, Pfc Edward R. Regione, Co. A, 262d Medical Battalion, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, dressed the wounds of the men and a start was made through the jungle. It soon became apparent that T/4 Winter could not make it even with two men helping him. He pleaded to be left behind. It was a hard decision for Lt. Williams to make, but the ANGAU men felt that they would find natives in a day or two who could be sent back to bring him out. Winter was carried on a litter to a dry, hidden place, wrapped in a blanket, and left with seven gallons of water, a case and a half of C rations, some morphine ampules with instructions for taking the drug if he felt it necessary, some sulphanilamide tablets, and his rifle. Here he was to stay, alone in the mosquito-infested jungle for fourteen long days and nights before a native from Arawe got to him by canoe and brought him back to Arawe.

Back in camp there was much anxiety about the outcome of the mission for one of the native police boys, wounded by jap gunfire, had fled from the party and had made his way alone through the jungle and back to camp four days after the encounter. He reported the attack and said he believed the men and boats were definitely lost. Gloom spread through out the camp. Two days later the 592d men could scarcely believe their eyes when they saw Lt. Williams and one of the ANGAU men walk into camp with the information that the rest of the group with the exception of Winter were only a short distance away at an Aussie Outpost. All of the men were weakened from their long six-day trek through the jungle but were otherwise in pretty fair shape. Immediately a native was sent by canoe to evacuate Winter. When he was brought back alive and little the worse for wear except for his wounded legs, they were overjoyed. Winter told them that after a few days his wounds had heated sufficiently to allow him to crawl to the barge wreckage where he found more rations and water. One day, he said, some American planes came over and, apparently thinking the barges were jap, bombed them to bits. That time he was really scared but his luck held. For variety, the next day a severe earthquake hit his area, but he lived through that, too. In telling his story Winter's spirit was inspiring. Despite his harrowing experience he joked about it and, upon his evacuation to Finschhafen, a news reporter asked him for a comment about his ordeal. He replied, "Oh! That two-weeks' furlough in New Britain?"

For his exceptional courage and heroism above and beyond the call to Duty T/4 Winter was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Along with Winter and Lt. Williams, who was later awarded the Bronze Star Medal, the Amphibs on the mission were S/Sgt. George J. McElvain, Bushnell, Illinois; T/4 Elmer J. Batsche, Newport, Kentucky; T/4 Herman E. Schneider, North Canton,. Ohio; T/5 Jack L. Minchey, Leonard, Texas; T/5 Edward Whitaker, Wichita Falls, Texas; Pfc Wilbur C. Charlton, Roundup, Montana; and Pfc Howard Calkins, Hampden, Maine, all of Company B, 592d EBSR and Edward Regione of Company A, 262d Medical Battalion, and of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

With all these Jap barges in the vicinity the most important job of the boatmen was patrolling, especially at night, to prevent a Jap surprise landing. Encounters with Jap planes were frequent. On the day after Christmas one of the LCMS, crewed by T/4 Clyde W. Eidson of Kannapolls, North Carolina, T/5 Fred L. Torres of Dallas, Texas, and Private Isadore Pahoski of Centralia, Washington, was struck by a falling jap plane. The plane swooped down in a strafing attack and the crew hurridly manning their guns, returned as much fire as possible. They evidently killed the pilot for the plane continued in its dive and crashed into the stern of their LCM. The barge did not sink immediately, but none of the crew could be found. After a thorough search in the barge, ashore, and in the water immediately surrounding the area failed to disclose any evidence of the missing men, they were presumed to have been blown up by the resulting explosion. In the same raid the 592d was credited with the destruction of another Jap plane.

The task group remained at Arawe and continued reconnaissance and patrolling missions until the first part of March 1944 when they were relieved. Arawe proved to be one of our "hottest" jobs.

On 26 December, 1943, the 592d boatmen, working this time with the famed 1st Marine Division, veterans of Guadalcanal, participated in two simultaneous landings on the western tip of New Britain near Cape Gloucester. One task group under the command of Major Rex K. Shaul of Akron, Ohio, landed marines on Green Beach, near Tuali only a few miles south of the objective Cape Gloucester airstrips. The other group under the command of Lt. Col. Ralph T. Simpson of Trenton, Tennessee, landed a force on Yellow Beach farther north and around the tip of New Britain. Both landings were successful and on the initial assaults only light resistance was encountered.

The Green Beach convoy of 14 LCMS, 2 LCVPS, and one Halvorsen patrol boat from Co. C, 592d, and 2 Rocket DUKWs from the 2d ESB Support Battery left Cape Cretin early Christmas night in the company of two destroyers and naval landing craft. A strange way to pass Christmas! They proceeded on a direct course to the rendezvous area and did not experience any unusual incidents enroute. Shortly after dawn the naval bombardment on Green Beach began. It continued for about fifteen minutes during which time the rocket DUKWs moved to a position nearer shore where they could cover the beach with a rocket barrage. After the naval bombardment stopped and before the rocket barrage started, two flights of B-25's bombed the objective beach. Then the rockets opened fire. While this firing was in progress the planes returned for another sweep of the beach. It was feared that some of the low-flying planes would be hit by the high trajectory fire of the rockets but luckily this did not happen. The DUKWS, under the command of 1st Lt. Walter D. Beaver, covered an area about four hundred yards square with a total of 240 rockets. The waves of LCMs and LCVs then landed the marines safely. Amber parachute flares were sent up to notify the Task Group Commander, who was still afloat, that the landing was successful. He was unable to see the actual landing due to the heavy smoke and dust cloud that covered the beach. The next few days were uneventful with only minor reconnaissance missions to spot ,enemy gun emplacements along the shore and to establish radio contact with the forces on Yellow Beach.

Late one afternoon the Japs counter-attacked with one of their hair-raising banzai charges. There was violent action until daylight when the Japs were repulsed with extremely heavy losses. The banzai charge is a substitute for mass harikari and has the hearty approval of every American. During this fight the marines suffered relatively few casualties and the Amphibs none at all.

According to a prearranged plan the Green Beach force was to evacuate all personnel and equipment from that area on 6 January and join the force on Yellow Beach. It so happened that the northwest typhoon season was just getting a good start. The high surf, rough seas, and stormy weather that it caused played havoc with the evacuation. Shuttle missions from Green to Yellow Beach were run continually for over a week by the Amphibs and not once during this period could the weather be classified as anything but "foul." On the first trip the seas were the most difficult the Amphibs had yet faced but they gained new confidence in their craft when they weathered the twenty-foot swells which had turned back the Navy's PT boats. The passengers took a beating as the small boats were tossed about by the mountainous waves like match sticks. The sheets of driving spray and rain did not add to their comfort either. The Ms and Vs were not designed nor intended to weather such seas, but the men had a job to do and they did it. The marines were landed.

During the evacuation, the 592d suffered several losses in landing craft. The poor condition of the beaches and the rough water took a heavy toll. No lives were lost. The prompt and skillful work of 2d Lt. (later 1st Lt.) Wilfred E. Poppen, Company C, 592d, of Toledo, Ohio, and his salvage detail in pulling broached landing craft off the surf-swept beaches contributed greatly to the success of the evacuation.

At Yellow Beach the 2d ESB boats were held in reserve on the initial assault but bad the usual resupply and reconnaissance missions thereafter as in previous operations. Shortly after the landing on D-Day a few jap bombers and Zeros came over to bomb and strafe the beach. They had an American A-20 right on their tails but they still managed to drop several bombs. The Zero dived low over the landing craft but was shot down by the .gun crews on our boats and on one of the LSTS. It was hard to determine just who got him so the Amphibs only claimed credit for half a plane.

Boat maintenance on Yellow Beach was their most difficult problem. The beaches were rocky and the waters offshore full of coral. Propellers were continually chewed up, shafts bent, and bottoms damaged as the heavy surf pounded the boats while they were being unloaded or loaded. Several times during strafing attacks and enemy artillery barrages the bullets and shell fragments opened fair-sized holes in the hulls. Improvisation was the rule rather than the exception on Yellow Beach. When anchors were lost because lines were cut on the sharp coral, the maintenance crews searched until they found a cache of jap anchors and a roll of jap steel cable. Although they were extremely light they worked out well and the worry over lost anchors was eliminated. 1st Lt. (later Capt.) Ellis M. Ivey, Jr. of Western Springs, Illinois, set up a boat maintenance detachment on Dot Island a few miles off Yellow Beach. A shortage of shipping space had prevented his bringing the usual heavy equipment for handling the barges. No M-20 crane was available to lift the sterns of the boats. As a result many a propellor was changed by divers working underwater in the heavy surf. Nevertheless, the boats were repaired and put back into operation in a remarkably short time. The job of the maintenance men is to keep the boats running and on Yellow Beach, despite the numerous difficulties, they did their job well. Later at Leyte Capt. Ivey was presented the Legion of Merit for his wonderful work and leadership.

The rocket DUKW on Yellow Beach, under the command of 1st Lt. Vermell A. Beck performed admirably. The first time they were called into action was when a marine advance was halted by a jap pillbox at a most strategic road junction. Access to the pillbox - other than by a frontal attack was impossible and that would have cost the lives of several men. When the DUKW was brought into range Lt. Beck fired only twenty rounds at the target. The story goes that the marine commander jumped up and down with joy when he looked at the damage it had caused. Many jap dead were found. On another occasion a DUKW shelled a deep ravine through which the Japs were passing. The japs, thought that they were well masked from artillery fire, but they evidently had not heard of the new American rockets. Over 200 Jap bodies were mute evidence to the effectiveness of the fire.

The DUKW was also used to rescue a wounded marine who was lying in an exposed position on a long, narrow sand spit extending from Natamo Point near Yellow Beach. Two marines endeavored to rescue him but, once on the sands pit, they were pinned down by enemy fire and could not get off. Landing craft volunteered to go to their assistance but sand bars prevented them from getting close enough. The rocket DUKW was called into action and the crew laid down a 105-round barrage inland from the sand spit. Under its protection the two marines crossed to safety. Unfortunately, the third marine was already dead.

The rockets were used quite frequently after that on various missions. Their performance on Cape Gloucester plus the fine work done by the 592d boatmen on re-supply and reconnaissance missions received high praise from Major General Rupertus, the Commanding General of the 1st. Marine Division. At a conference of all unit commanders early in January, the General stated in effect:

"Gentlemen, you have more than upheld the fine tradition of the United States Marines. You have done a wonderful job and I congratulate you. And that is not only true of the United States Marines, but of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade as well."

During the month of February the 592d detachment on Cape Gloucester received many casualties due to air attacks - both by jap and American planes. One LCVP was sunk when it received a direct hit by an enemy bomb and two nearby LCMs were severely damaged by shell fragments. One officer and four men could not be located and were presumed to have been killed in the attack. On two separate occasions American pilots who must have mistaken the 2d ESB craft for enemy barges zoomed down in strafing attacks. When they came close enough to see the flags and identifying insignia on the boats they immediately ceased firing, but their aim was good and usually by the time they noticed their error, it was too late, and members of the boat crews were already bit. It was just one of those unfortunate accidents of war. Fortunately, by keeping as close liaison as possible with the Air Force, only two such attacks occurred.

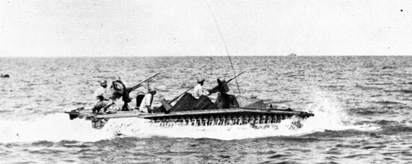

Bristling with armanent, this “Buffalo” served as support

during invasion landings. Manned by Amphibian Engineers,

its many guns were used to repulse attack from land, sea, or air.

Saidor, New Guinea. 2 January 1944.

Unloading artillery ammunition from

Co. B, 542 EBSR LCM.

Saidor, New Guinea. 2 January 1944.

One wave of Co B 542 EBSR, LCMs heading for the beach.

The 2d ESB boats landed several marine detachments at various beaches along the northern New Britain coast from Yellow Beach as far east as Talasea, 160 miles nearer Rabaul. On this landing they worked with a detachment of the 3d ESB and the cooperative, rather than a competitive, spirit that existed between the men of both brigades was very evident. On the first of May the Cape Gloucester operation was declared to be successfully concluded and the 592d detachment returned to its regimental area at Oro Bay.

On the same night that the 592d boatmen landed the marines on Cape Gloucester, another 592d provisional group, consisting of Company D and some attached medics and boatmen and an Australian radar detachment, effected a successful landing of their own on Long Island. That small island, 105 miles north of Finschhafen and at the head of the Vitiaz Strait, provided an excellent location for radar installations and a lookout station. The task group of about two hundred officers and men under the command of Major (later Lt. Col.) Leonard Kaplan of Hempstead, New York, proceeded to Long Island on PT boats, arriving there shortly after midnight on 26 December. The men went ashore in rubber boats. A passenger on a rubber boat always has the feeling that the slightest movement will cause it to capsize and during this landing the sea was not calm. Actually two of the boats did capsize in the surf but, luckily, no men or equipment were lost.

As they had been told to expect, the landing was unopposed. Three days before the actual landing Major Kaplan and two amphibian scouts had reconnoitered the island and found no trace of enemy occupation. This landing was the deepest allied penetration into jap-controlled territory up to that time and the absence of opposition was a disappointment to the shore engineers who were well armed and anxious for a crack at the enemy. It turned out that while the Japs had never garrisoned Long Island; it had been used as a staging point for jap barges enroute from Rabaul to Wewak. Our seizure of Long Island stopped this traffic.

Since the island was some distance from the New Guinea mainland the resupply of this task group was a difficult problem. Several LCM convoys carrying rations and supplies made the trip through the rough seas to Long Island the next few weeks and PT boats frequently dropped off supplies, but for the most part the detachment was left entirely alone. The men did not mind this a bit, for although life was somewhat boring, the natives were friendly, the island with its twin mountain peaks and large volcanic lake was beautiful, fishing was good - and there were no Japs. The detachment remained on Long Island almost two, months during which time they set up the radar station and constructed a cub airstrip. Otherwise they just held the island and defended it against Japanese occupation. One night a flash flood caused by torrential rains caved in the bank where one of the bulldozers was parked. It fell into the usually shallow stream, but the flooded stream now had so much power it washed that heavy dozer away. It was never found.

With the landings on New Britain and Long Island so successful, General Krueger's Sixth Army followed up with another landing, this time at Saidor between Sio and Madang on New Guinea's north coast, to cut off the Japs retreating from the Huon Peninsula. Under the Command of Lt. Col. Robert J. Kasper, the Shore Battalion of the 542d EBSR and a small boat detachment of 6 LCMs plus 2 Rocket DUKWs landed at Saidor with troops of the 32d Infantry Division on 2 January 1944. The landing was also unopposed. The task group left Goodenough Island on 31 December and traveled over New Year's day stopping at Finschhafen only long enough to pick up and tow to the objective area a dozen LCMs loaded with the two DUKWs and bulldozers.

The next morning there was the usual naval and aerial bombardment on the assault beach after which the troops went ashore. Inasmuch as this was primarily a shore operation for the 2d ESB, every step of the planning was aimed at the elimination of waste time in the unloading of the large landing craft. The reconnaissance parties went in on the first waves to select sites for supply dumps and the best routes for exit roads from the beach. The bulldozers brought in on the first few waves had already cut these roads and cleared dump areas when the six LSTs landed. The beach was covered with rocks the size of turtle eggs and vehicles coming off the LSTs had difficulty in getting enough traction to cross it. When Colonel Kasper noticed this, he stopped the unloading for a few minutes while pathways were cleared and from then on everything went like clockwork. Assisted by the infantry and even the Navy personnel on the LSTS, the 542d set a new record in the unloading of the six LSTS. It took exactly three hours! The careful advance planning, the cooperation of every unit, and the absence of enemy opposition made this record possible.

Except for one engagement in which the Support Battery's two rocket DUKWs under 1st Lt. (later Capt.) Edwin T. Stevenson of North Plainfield, New Jersey, participated, the Saidor encampment had a peaceful existence. On the third day after the assault the two DUKWs were loaded on LCMs and, proceeding to Biliau Village further up the coast, they fired 360 rockets which completely destroyed all buildings and exploded a large Jap ammunition dump. Upon completion of this mission the DUKWs returned to their base at Cape Cretin.

Saidor, New Guinea. 2 January 1944. LCVPs of Co B, EBSR,

carry assault troops to the beach through the surf.

Although the first few days of the Saidor detachment were devoid of serious trouble, it could not last forever. The same storm that caused several 2d ESB landing craft to be wrecked on Cape Gloucester also brought heavy rains on Saidor. As a result the roads became mud holes and the dumps became bogs. The rain did not actually hurt anyone, but it and its resulting mud did make life very, very uncomfortable.

The 542d received one casualty death but that was not due to enemy action. On the night following the landing one of the men got up and wandered from the camp area. A sentry, who could not see him clearly in the dark shadows, challenged him several times. When there was no response, the sentry figured him to be a Jap infiltrator and fired. It will never be known whether the man was sleep walking or tongue-tied with fright when challenged at the point of a gun. Strange and unfortunate accidents occur in time of battle.

The possibility of using decoy landing craft to distract the enemy planes from the real boats had often been discussed by the Amphibs. Why not try it? At Saidor thev did, but with quite unexpected results. Several dummy barges built of canvas were located in a partially camouflaged position up the coast from the true anchorage. The airforce was told of the plan. However, a friendly reconnaissance pilot spotted them and, figuring they were most certainly jap barges, relayed the information to his commanding officer. Within an hour our own aircraft were strafing and destroying the decoys. If the assumption that anything that fools our Air Force will certainly fool the japs holds true (and it is usually correct) the plan is feasible. However, it was not tried again and the subject merely became "one for the book."

When the Saidor operation was closed early in February, the 542d detachment with the exception of Company B returned to Oro Bay. On 5 March Company B with 75 LCMs and LCVs attached from the 3d ESB landed two infantry battalion combat teams on the beach at Yaleau Plantation northwest of Saidor. PT boats. and rocket LCVPs shelled the beach prior to the landing. There was very little enemy opposition and the landing was made without incident.

Meanwhile, the 5th Australian Division and the 532d boats were pushing their way up the coast from Sio. They contacted the forces working east from Saidor on 10 February to bring the entire New Guinea coast line as far north as Saidor under allied control. On this advance the 532d boatmen had several unusual experiences. 1st Lt. Edwin T. Foster, Co. A, 532d, of West Orange, New Jersey, while engaged in reconnaissance of the forward beaches, discovered two Australian DUKWs stranded on the beach near Lepsius Point which was still enemy territory at the time. Thirteen Australian troops, the crews and passengers of the DIJKWS, were apparently surrounded by the enemy but Lt. Forster landed and assisted in refloating one of the DUKWS. The withdrawal from the beach was covered by two flak boats in his detachment. On the return trip they were fired on by enemy machine guns and his boats received several hits. The flak boats opened fire immediately and in a few minutes the enemy guns were silenced. Australian scouts later reported finding the abandoned guns, and one dead jap. This was the first time the brigade's flak boats were used in combat. They are LCMs mounted with four Martin Turrets with twin 50-caliber machine guns, a 37-mm gun, two 20-mm guns, and rocket launchers. Designed by Major (later Lt. Col.) Elmer P. Volgenau and built by men of the 162d Ordnance Maintenance Company to give added fire support to the landing craft convoys and reconnaissance patrols, the flak boats showed their usefulness on their first mission. Since then they have been used constantly on all missions and have established for themselves a long record of destroyed enemy planes, barges, and personnel. Several newspapers in the states commented on "General Heavey's battleships" pointing out that pound for pound they bad greater fire power than a real battleship.

Landing Diagram Red Beach

Two other incidents on this advance resulted in the capture of two Jap prisoners. One Amphib patrol from Company E, 532d, came on a Jap going through the pack of a comrade who bad been killed by the natives. They approached him with extreme caution and then with a sudden rush, they pinned him to the ground. He was turned over to the Australians for questioning. On another day two other Amphibs from the same company were swimming in a river near Sialum when an Australian patrol told them there was a dead Jap up on the beach. Always curious they went to see him, but he wasn't dead! When discovered, he made a rush for a cave near him. Here was a situation. Should the men, unarmed, follow him into the cave where they might possibly be ambushed by other armed Japs, or let him go? They could see ammunition, a bayonet and other equipment, at the mouth of the cave so they carefully fished it out with long poles. After a cautious search they found another entrance to the cave and the Jap, alone and apparently unarmed, could be seen inside. They drove him out with rocks, one of the men hitting the Jap on the head and knocking him out. He was turned over to the Aussies.

The Arawe and Gloucester landings on New Britain had made the Japs think the Allied Forces were headed for Rabaul, the key fortress to the Jap defense system in the Solomons and Bismarck Sea areas. In October the Air Force began a full-scale and an unremitting attack on the Rabaul bastion. Occasionally naval units would approach that base and shell the area relentlessly. To strengthen the idea that Rabaul was the allied objective, the Marines from Cape Gloucester continued their thrust along the northern New Britain coast as far east as Talasea, 160 miles east of their initial beachhead. Yes, the Japs had every reason to believe - and fear - that Rabaul was next. Captured Jap diaries later revealed that they were so certain of attack that every spare moment was spent in setting up their installations inside deep mountain caves. But much to their surprise the next blow fell - not on Rabaul - but on the Admiralty Islands.

By virtue of their successful landings on Long Island and at Saidor, the Yanks and Aussies controlled the entire Huon Peninsula. This provided then with protection from the rear during the three hundred-mile dash from Finschhafen to the Admiralties. Control of Western New Britain gave protection on the right flank. Plans for the assault were made and the American occupation of the Admiralties began the last day of February 1944.

On that day a reconnaissance force from the 1st Cavalry Division landed in the vicinity of Hyane Harbor on the island of Los Negros. There was little opposition and by nightfall of the first day this force had established a beachhead fronting on the Momote airstrip only a short distance inland. Realizing that enemy forces were in position across the strip, they did not press their advance further until the main attack force landed two days later to support them.

The participation of the 592d EBSR in the Support Task Force began only a few days before they actually embarked. Major (later Lt. Col.) Kaplan, the Shore Battalion Commander, received sudden orders late in February to prepare certain units of the regiment for an immediate combat mission. Company E, with Captain (later Major) Henry M. Seipt Jr. of Riverton, Wyoming, in command, was expanded into a provisional task group by the addition of Medical, communication, and weapons sections. Six LCMs and six LCVs represented the Boat Battalion in this initial mission. As the operation progressed and new landings on the surrounding islands were made, more men and boats were sent to the Admiralties.

With the exception of slight and only intermittent hostile fire during the approach to the beach, the convoy arrived about noon on the second of March without incident. Immediately the shore engineers set to work with their bulldozers constructing LST ramps and dump areas. Roller conveyors were erected deep into the throats of the LSTs that somehow resembled huge dead whales with their mouths open and massive lower jaws resting on the beach. The unloading did not go off as smoothly as was anticipated because enemy fire still raked the narrow beach every once in a while causing a congestion of personnel and vehicles.

However, before darknss fell the entire convoy was unloaded and the men prepared to, "dig in" for the night. During this process of "digging in" a corporal of one of the machine gun sections working on his emplacement was killed by the accidental discharge of his rifle. Warned to anticipate infiltration, the 592d engineers obeyed orders to remain in foxholes throughout the night; there was no evidence of "trigger-happiness" on their part though small arms fire continued on the cavalry perimeter as they repulsed successive enemy patrols.

The next morning the Momote airstrip was completely cleared of the enemy. Their casualties of the night before, which must have been considerable, had apparently been taken back with them. As the cavalry moved along the coast to cut off the Japs on the jamandilai Peninsula, the protecting arm of Hyane Harbor, the Amphibs were busy moving the piles of supplies to a new and more permanent dump area. They moved their CP and set up a new perimeter defense system for their second night ashore. A large counterattack was expected and orders were issued for every man to sleep in his foxhole again and for the guards to fire at anything moving above ground from dusk until dawn.

At approximately three o'clock the next morning the enemy with a force of about fifteen hundred men stormed the right flank of the Yank perimeter. They found the Cavalrymen and Amphibs waiting. Every available weapon was brought to bear on the japs as they charged time after time. The 592d men were constantly active and their guns kept up a steady stream of fire. At daylight there were almost two hundred dead japs piled in front of the perimeter and it is believed that many more casualties had been dragged away. How many of these were killed by Amphibs we will of course never know. An hour after day break, fifty japs shouting hysterically and singing "Deep in the Heart of Texas" charged the perimeter in suicidal frenzy. Not one survived.

But the fighting was by no means one-sided for a check up of the 592d personnel revealed one officer and three men killed and several wounded. Most of these casualties were received at one time when the engineers had taken a temporary refuge with some cavalrymen in a dugout. Suddenly two tommy gunners appeared at each entrance to the dugout and sprayed the inside with .45 caliber slugs. Perhaps the gunners were jap. Perhaps American. The mystery remains, but the bullets killed all the same, sad to say.

Although there were many instances of individual heroism by the men of the 592d detachment in the defense of the beachhead that night, there is one incident that is outstanding. Three times during the fighting the cavalry and engineers withdrew to prevent being cut off by infiltrating japs. In this withdrawal movement they took the bolts from the machine guns and their ammunition, but left the guns in their defensive positions. From their new line of resistance they repulsed the Jap attack and later, when the situation permitted, returned to their forward gun emplacements. One gunner, Corporal Joseph E. Walkney, Co C, 592d EBSR, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, obeyed these instructions but with reluctance. He could not see the sense in leaving his gun in the face of an attack. The idea to go back to his gun obsessed him until he couldn't resist. Grabbing a bolt and some ammunition he cautiously crawled back to his old gun position. The rest of his crew tried to stop him but he paid no attention. Singlehandedly he put his weapon into action and waited for an appropriate target. It was a dark night and he could scarcely distinguish the swiftly advancing forms of jap infantry, but he could hear their blood-curdling screams. There they were-right in front of him! His left forefinger squeezed the trigger and his gun sputtered a trail of hot lead. Corporal Walkney did not live long enough to see the damage he had caused or even to know that he alone had smashed the jap charge. At dawn he was found dead behind his gun. In front of it many dead japs laid sprawled in grotesque positions. Undoubtedly he had wounded others who had very probably crawled from his line of fire only to be killed by someone else's bullet. Through his efforts there was no break through the American defense lines that night.

The next few days were rather uneventful - the camp area was improved, the beach was prepared for the next echelon of LSTS, and maintenance was done on all boats, and vehicles. When the LSTs arrived they brought with them five more badly needed LCMS, including one flak LCM, and four LVTs of the Support Battery. One of the LVTs was equipped for rocket firing and was under the command of 2d Lt. (later 1st Lt.) Donald B. Davis of Chicago, Illinois. Immediately every available craft was requested by the cavalrymen for a series of end runs and reconnaissance missions in and around Seeadler - Harbor on the north coast of Los Negros. They made their first attack on Papitalai Plantation located on a peninsula that jutted out into the harbor. Firing rockets and strafing the beach with automatic weapons, the combat LVT and the flak LCM, under the command of 2d Lt. (now 1st Lt.) George W. Hawk, Hq. Co. Sh. Bn., 592d, of Tulsa, Oklahoma, smashed all enemy opposition and led the first waves of LCMs to the beach. Thirty casualties. including twelve "good" japs found in a bunker untouched save for their eyes blown out by the rocket's concussion, were definitely credited to the LVT. Throughout the day the landing craft shuttled back and forth bringing troops to the new beachhead. It was a most successful mission.

Here was a turn of events that favored the Yanks. With added firepower, the effectiveness of which had just been displayed, they could send reconnaissance missions deep into the enemy's defense line. They pressed their advantage well. The Japs never knew where the next blow would strike and they came so rapidly one after the other that they had little time to prepare an adequate defense system. In rapid succession the Yanks landed on Lombrum Point, Bear Point, and two small islands of Butjo Luo just off the coast of Manus Island - the largest of the Admiralty group. In each of these landings they encountered little opposition.

Meanwhile the rest of the 592d Shore Battalion and some additional landing craft from the Boat Battalion had arrived. The shore operations and reconnaissance missions assumed an increased tempo as more supplies were rushed to the new American base. The spirit seemed to be "When you've got them on the run, keep pushing." - and that's exactly what they did.

As far as the Amphibs were concerned, the outstanding exploit of these stepped-up operations was the first landing on little Hauwei Island a few miles out of Seeadler Harbor and just north of Manus. Here one of the LCVS, coxswained by T/4 James C. Breslin of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, covered by a single PT boat, landed a reconnaissance patrol of some twenty-five cavalrymen on 11 March. Aerial photos of the island and information from friendly natives indicated the island was unoccupied. However, the Japs were there in force and very cleverly concealed. They allowed the cavalry patrol to land and then ambushed them as they pushed inland. Other Japs opened up on the PT boat and the lone LCV. The landing barge was armored and managed to turn the enemy fire but the PT boat was forced to retire. Sergeant Breslin, seeing the patrol in trouble on shore, headed his boat back to the beach and, although, under continuous fire the full distance, he succeeded in picking up eight survivors, five of whom were wounded. Retracting from the beach he spotted another group up the beach who were frantically signalling for his assistance. Again he pushed his craft to the shore and succeeded in picking up those men. He retracted a second time. Meanwhile, Jap mortar fire was hitting all around the small boat which veered to the right and then to the left to throw the Japs off their aim. Their luck ran out for a shell hit very closely and fragments penetrated the boat's armor. It began to sink. The crew during this time had managed to get life jackets on all the passengers, including the wounded. Sergeant Breslin, who was now seriously wounded, set the engines at full speed and went as far out to sea and out of range of the enemy fire as he could before the boat went down under him. All personnel floated clear.

When the PT boat arrived back at the base they reported the ambush and indicated that they believed every man had been killed. However, a bomber was sent to investigate the scene just in case the unexpected had happened. When the pilot sighted the survivors bobbing around in the water, he radioed back the information and soon rescuing craft were on the way. The LCM’s crew Sgt. Breslin; Sgt. Franklin Armstrong of Muskegon, Michigan; Cpl. Walter Wilson of Spartansburg, South Caroline; and Private Henry Renfroe of Curly, Alabama were highly praised by the cavalry commander for their heroic action. The next day a cavalry force, supported by three LVTS, one flak LCM, and two rocket LCVS, made a successful landing on the same beach and wiped out the entire jap garrison. Observers said that the rocket assault was the heaviest yet launched in a pre-landing barrage.

A few days later another large scale landing was run off when the cavalrymen were landed on Manus Island with the Lorengau airstrip as their primary objective. Again the buffalos, rocket Vs, and the flak M had a field day as they laid down a preliminary barrage on the objective beachhead. The actual landing was unopposed, but several Jap bodies and the appearance of the camp area were mute evidence that the Japs had departed rather hurriedly. The cavalrymen lost no time in advancing through the jungle and in a few hours the airstrip was won. During this operation Sergeant Harold P. Waldum, Hq. and Service Company of Black River Falls, Wisconsin, was a gunner on one of the LCMs on a resupply mission up the coast to the forward elements of the cavalry. Enroute he observed several casualties awaiting evacuation on the beach. Japs in the hills behind the beach had spotted the helpless group and were covering the beach with an intense machine gun fire. Escape seemed out of the question. Sergeant Waldum, immediately manned the gun on his craft and from an exposed position he delivered an accurate and prolonged fire on the enemy, thus enabling the boat to approach the beach, obtain the wounded men and withdraw. He was justly awarded the Silver Star Medal.

A few days later the rocket and flak boats returned to Lombrum Point where a small enemy force had been detected. Over one hundred rockets and thousands of rounds of ammunition from the automatic weapons were fired into the enemy camp. Several pillboxes were destroyed and the enemy was forced to retreat over the ridge where they were decimated by waiting American troops.

The march continued as island after island was mopped up. Tremendous rocket barrages followed by cavalry assaults on the several beaches was most effective. Pityilu, Koruniat, and Ndrilo Islands north of Manus were seized without much struggle. In rapid succession invasions were made on the islands of Rambutyo and Pak on the southern fringes of the Admiralty group. In all of these operations the boatmen and cavalrymen worked in close cooperation. Detachments from the shore party participated in each assault to unload supplies. construct roads, evacuate casualties and maintain the dump areas. Opposition on all of these islands rapidly diminished until it was entirely eliminated. Not a jap remained.

The latter part of April, orders were received for some of the 592d units to make preparations for a new and more far-reaching operation. The islands of the Admiralty Group were now in American hands after a highlv successful campaign in which the ratio of enemy dead to the American was better than fifteen to one. An invaluable base had been cheaply gained and was quickly being put into operation for the continuing land, sea and air offensive against the remaining jap bases barring the way to Tokyo.

The 592d had won the respect and admiration of the 1st Cavalry Division. The Amphibs and the Cavalrymen were destined to be together in many important operations to come. The close feeling of comradeship and mutual confidence in each other established in; the Admiralties were to pay dividends later in the Philippines.

|