Chapter IV

Baptism of Fire

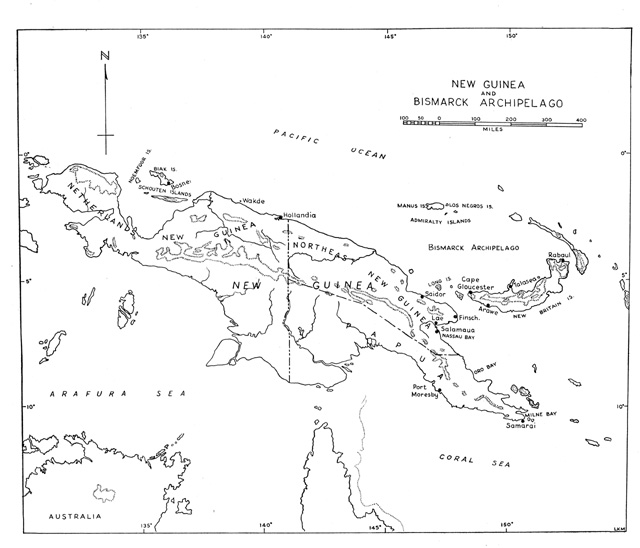

NEW GUINEA, the land of the Fuzzy Wuzzy, was to most Amphips little more than a place on the map that they had read about in their eighth grade geography until the Japs started their invasion in 1942. Then it became a focal point of world attention. Divided into two parts, with the Dutch controlling the western half and the Aussies the eastern, New Guinea is the world’s second largest island, famed for it’s lofty Owen-Stanley mountain range and its vast mineral deposits. It is also famed for some of the worst jungles in the world. Roads are practically non-existent. Malaria, scrub typhus, and “jungle rot” of the skin are much worse enemies than the touted cannibals of the interior ever were. Actually the natives we encountered were, on the whole, friendly and helpful. Its shores offer some long stretches of excellent landing Peaches but at many areas, massive sharp coral reefs make the beaching of landing craft almost an impossibility Viewed from the air these reefs are jewels of beauty with their vari-colored shades of green, yellow, purple and violet. To our boatmen seeking a landing beach, they had no beauty.

When the Amphibs were first informed that New Guinea was to be their ultimate destination their first request was for coastal charts. They got a rude shock when they were informed that the only charts obtainable were very sketchy and unreliable. The brigade coxswains quickly discovered the truth of that statement, although, throughout the entire New Guinea campaign, the cautious manner in which they maneuvered their craft kept boat damage due to crashing on some uncharted reef at an absolute minimum. It was simply a matter of feeling their way along and then charting the beaches themselves. Another surpnising element with which they had to contend was that the tides were unpredictable. Instead of the high and low tides which could easily be determined in the States from prefigured tide tables, here in New Guinea nature was a freak on tides. We were so close to the equator that neither the time nor the amount of the tide could be predicted. Usually there was only one high tide a day instead of two. Such was the terrain of New Guinea, the land of searing sunshine and torrential rains, of malaria and skin rot, where the Amphibs were to make themselves “at home” for the next year and a half.

Col John JF Steiner, CE, Commanding 582nd Engr Boat and Shore Regt, 1 October 1942 to 11 February 1944. Col John JF Steiner, CE, Commanding 582nd Engr Boat and Shore Regt, 1 October 1942 to 11 February 1944.

For the sake of the record and to settle an argument between two Amphibs that was overheard recently, a detachment of the 592d EBSR was the first brigade unit to pitch camp in the New Guinea mud. It’s true that several officers and men, including the General, Col. Steiner, and Lt. Col. Brockett, had made prior reconnaissance trips to New Guinea, but they returned to Australia with their reports and cannot be counted as a “permanent unit.” in the first week of May, 1943, this small detachment of ten LCMs under 1st Lieutenant (now Captain) E. S. Schenk, 562d EBM Battalion, of Greensboro, North Carolina, moved by Liberty ship with ten used LCMs from Brisbane to Port Moresby. From there they were to run missions to the mouth of the Lakekamu River over one hundred miles westward. Seven of the LCMs were later routed to Milne Bay to perform lighterage duties there.

The Aussies, firm in their belief that the Japs had a large concentration of supplies in the vicinity of the Wau gold fields, were constructing a road over the Owen-Stanley Range from the village of Bulldog, thirty miles up the Lakekamu River, to that base. They figured that supplies for the attacking allied troops could easily be taken up the winding Lakekamu River to Bulldog on flat bottom barges. Using Yank engineer equipment they had made fair progress until the New Guinea April showers converted the small creeks and rivulets into raging torrents and their roadway into a flooded area. The project had to be abandoned. The LCMs then had the job of bringing back to Moresby all useful engineering equipment.

Their first trip along this strange, uncharted coastline was full of excitement. Two LCMs started out one night from Moresby each with a native guide on its bow to direct the boat’s course through the coral-reefed waters. Jap air attacks were frequent enough to make daylight trips in these waters rather dangerous. Although progress was exceedingly slow, the boat crews were amazed at the natives uncanny skill of direction. Captain Schenk admits that at one time when his guide pointed dead ahead and whispered to him “Light”! it was fully half an hour before he could see that light even through his powerful night glasses. When they reached the mouth of the river they encountered other problems. The surf was unusually heavy. There was a three-foot sand bar over which the LCMs could pass only two hours out of the day and, once inside the river, they had to stay until high tide returned. The trip up the river to Bulldog was an experience in itself. The river wound and twisted so much that to cover the thirty miles “as the crow flies”, they had to travel over one hundred miles on the river. Logs, rocks, and dense overhanging jungle made their trip even more dangerous. An occasional crocodile glided by. There was also the constant threat of a Jap air attack and several times they were forced to scurry for the shelter of the river bank. On one occasion a Jap plane swooped down on two of our boats in a strafing attack. The only damage was a couple of bullets in a box of bully beef. The men on the boats said that the bully beef was so tough that even bullets couldn’t go through it!

Port Moresby had no maintenance facilities for our boats. The detachment from the 562d Boat Maintenance Battalion ingeniously solved some maintenance problems “on the spot.” To change props on the boats they constructed log barriers on the beach at low tide and brought the boat over the barrier at high tide. When the tide receded, the boat was left high and dry and the prop could be changed easily. It was a slow process but their job was accomplished. Another of their problems was the procurement of necessary small parts for the boats, but always their Yank ingenuity offered a ready solution. At one time they were in dire need of rubber strut bearings. None were available. To wait for a shipment from Australia was out of the question. The boats must be kept running. The bearings were made of wood, “New Guinea Iron wood”, probably one of the first instances of wooden bearings for shafts of landing craft. The Moresby detachment continued to function until late August when all the personnel and craft were sent to Milne Bay to assist in lighterage duties at that base.

During the early fall (March is fall south of the equator) General Heavey, in anticipation of coming brigade operations along the New Guinea coast north of Milne Bay, reconnoitered for a base in the vicinity of that bay to be used as a staging area for brigade troops and as a maintenance area for brigade landing craft on their way north from Australia into combat. The Milne Bay region was selected because it was the most advanced point to which the Navy would agree to send large ships capable of carrying landing craft. The island of Samarai was selected as the best site for a base of this sort.

Samarai is approximately a mile long and a half mile wide. As one of the two ports of entry for Australia in New Guinea before the war and the seat of the Papuan Government, Samarai, in spite of its small size, had been a port and town of considerable importance. It was the only approximation to a Hollywood South Sea island we ever encountered and even then the likeness was not startling. The business district had been demolished by the Australian Military Forces at the time of the Japanese invasion of Milne Bay but the majority of the private residences and the hospitals were still intact and available for use by the occupying troops. Water supply was assured by rain water cisterns. Mosquitoes were rare on this island. Tropical flowers were in profusion.

Approval of the plan and site having been received, Lieutenant Colonel Allen L. Keyes (now Colonel) of West Point, New York, formed a detachment of about three hundred men from the 542d EBSR, embarked at Townsville, and proceeded to Samarai early in June. The landing was effected quickly for natives claimed a Jap submarine had surfaced near the island two days before, apparently to charge its batteries. Their first job after setting up camp was to establish a small boat maintenance shop and to build a dock on the site of the old government wharf which had disappeared during the “earth scorching” by the Aussies. Concealment areas for over three hundred landing craft and camp areas for three boat companies were selected and prepared on the neighboring island of Sanbi. However, military operations advanced too fast for the Samarai base to attain the importance which had been foreseen. The Navy relaxed its previous restrictions after the completion of the successful Nassau Bay landing in which the 532d EBSR played an important part. The landing craft could then be deckloaded all the way from Cairns to Oro Bay eliminating the necessity for any stop at Samarai.

Every participant in the Samarai mission remembers well the very cordial relationships that existed between the Amphibs and the Aussies stationed near Samarai. The shop facilities of each unit, were extended to the other and on several occasions the Aussies performed machineshop work for the Amphibs that was beyond the scope of the simple equipment the engineers had. To show his appreciation for this cooperation Colonel Keyes invited them to share their Fourth of July dinner and to play soft ball and cricket with the Amphibs in honor of Independence Day. It would not be truthful to say that we won at cricket, but all enjoyed it.

Oro Bay, New Guinea. Sign post on the road to Tokyo.

All units of the Brigade staged from Oro Bay for various

operations from May 1943 to June 1944.

Colonel Keyes tells the story of how his encampment was awakened early one morning by the sound of several shots echoing in the night air. Upon investigation one of the perimeter guards admitted firing the shots and gave the excuse that he had seen a “man on horseback” galloping down the road at breakneck speed and, when he failed to heed the order to halt, he had fired. Unfortunately the guard missed and there was no evidence to support his story. The next evening the performance was repeated by another guard. His story was the same. It seemed strange that no one else ever saw this “man on horseback” who may have been Sleepy Hollow’s “Headless Horseman” returning to haunt a new world. The guard was increased and instructed to capture the intruder when he next appeared. He never did. Colonel Keyes said that a few days later he congratulated his guards on their vigilance, but with the next breath he expressed his regret at their poor marksmanship.

By the end of July the detachment had received sixty LCVPs from Australia. When orders were received to move to Oro Bay, there were not enough crews to man all the craft, the shipment of boat companies from Australia having been delayed. However, the trip had to be made immediately, so engineers and seamen became coxswains overnight and shore personnel and even medicos were used to fill out the crews. Loading every barge to capacity they started out and soon were past Milne Bay and around the north coast. All went along nicely until nightfall, then the storm came. The inexperienced crews faced a most severe test and over half of them lost their formation and scattered in all directions. At dawn the storm abated and the “lost” boats anchored in the safe harbors of Goodenough Island. One of our boats hit a coral reef and was damaged so that it could not continue the trip. It was stripped of its engine and all salvageable equipment but the hull had to be abandoned. Nature, as much an enemy to us as the Japs, had claimed its first victim from us. Colonel Keyes admits that he spent many anxious moments in rounding up his boats but the job was soon accomplished and the convoy proceeded on its way to Oro Bay. On every convoy since then a fast command boat has gone along to keep the other craft in formation even in the roughest seas.

As the memory of the Samarai detachment fades into history, the brigade often looks back on the lessons learned there, the friendly associations with the Aussies and those hot, humid working days. Inexperienced in the rigors of jungle life, the Amphibs soon got used to days of alternating tropical heat and rain and, like engineers who are happiest when constructing something, never displayed fatigue as long as they could “watch things grow.”

The first brigade unit to become engaged in actual combat with the enemy was a detachment of the 532d EBSR that was sent to Oro Bay in May, 1943, to join forces with the 41st Infantry Division. Their craft were deckloaded as far as Milne Bay, but at that point they were forced to unload and proceed under their own power as the Navy considered waters beyond Milne Bay too dangerous for large ships. Brigade boat crews took over the barges and ran them more than two hundred miles up the costline to Oro Bay in their first long run through the coral-reefed waters with which they later became so familiar, On this trip they also received their first baptism of fire, although it came from an American not a Jap machine-gun. Most of the Yanks fighting in New Guinea had seen much more enemy activity than allied up to that time. Despite advance notice that American barges would arrive that night at Oro Bay, a gunner with an itchy trigger-finger was sure those strange craft approaching out of the night and blinking recognition signals to the shore were Japs trying to fool him. He was an accurate gunner, too, for his second burst pinged against the boat’s armor. Fortunately, however, no one was injured and the boat crews were convinced the armor of their boats would turn small arms fire and American ammunition at that. This knowledge was often very comforting in later operations. The numerous bombed and wrecked ships in Milne Bay and Oro Bay were mute evidence to our boatmen that they were now in combat areas. At night lights were blacked out. Red alerts were frequent.

New Guinea, September 1943. “Moby Dick Jr.” the 2 ESB’s only

plane, given up after being cracked up by Air Corps

pilot on both of its flights.

Shortly after their arrival in Oro Bay the brigade suffered its first personnel casualties due to enemy action. On the night of 18 June 1943, Jap planes dropped five “daisy cutters” in their camp area. When the shock had subsided the first thought of every man was, Was anyone hit? The sudden realization that the greatest misfortune of war had struck in their midst came to them when they moved away the debris and found one of their buddies, Technician Fifth Grade Harold L. Nelson, Co. A, 532d EBSR, of Horrick, Iowa, killed; our first battle casualty. Four other men were wounded. We resolved the Japs would pay for his death; everyone redoubled his efforts.

While the Amphibs were assembling and training in Australia from February to May, 1943, elements of the 41st U. S. infantry Division were busy on the upper side of the southeastern tip of New Guinea pushing the Japs back along the shoreline from Buna. The southward surge of the enemy invaders had been definitely halted in the bloody battles of Milne Bay, Buna, and Sanananda. The Yanks and Aussies took up the offensive but their advance was slow and uncertain due to lack of landing craft for coastal supply and for making “End runs” around the Jap’s strong defense lines, The Japs and Americans were locked in a struggle for supremacy in the skies over this area. It was definitely not safe to expose a large ship to Jap air attack in the waters around Buna. The same situation applied to Jap ships as the bombed wrecks in these waters clearly showed.

The Amphibs were anxious to go to their assistance but were unfortunately not yet equipped with landing craft. If the boat assembly plant in Cairns had been in operation upon the Brigade’s arrival overseas, there is no doubt but that the brigade would have been in combat several months sooner. They were urgently needed and anxious to get into combat, but the lack of landing craft stymied them. As rapidly as the boats came off the assembly lines at Cairns in April, 1943, and the boat operators were given an opportunity to refresh in their minds their earlier boat training, special detachments were formed and sent to the combat area. By early June three such detachments were already in operation in New Guniea, Port Moresby, Samarai and Oro Bay. The rest of the brigade continued training at Cairns with the Australians and champed at the bit to get going against the Japs.

While these detachments were getting themselves established, plans were being made for the brigade’s first combat operation. This was a small-scale job compared to the amphibious strikes destined to come later, but it included practically all the adverse elements that can rise to plague an invasion operation; raging surf with its resultant loss of boats and supplies, unfavorable terrain ashore, heavy enemy opposition, serious resupply difficulties and death.

By the end of June the Oro Bay detachment had established a small base for operations at Morobe about midway up the coast from Buna to Salamaua, the latter being operated by the Japs as a principal supply base. Morobe was famous for an unusual tragedy. One day a couple of doughboys were sunning on the beach. Suddenly a streak like a submarine came in from the sea. It was a crocodile. Before the men could get away, the crocodile grabbed one by the leg and dragged him off to sea, never to be seen again. Before our move to New Guinea we had been warned of the ferocious crocodiles and sharks we would encounter. Outside of this one incident we did not actually have any encounters with “crocs” or sharks. The men rarely saw any and found that when they moved in a new area, the animals invariably moved away and left the area to man. The bugs and mosquitoes, on the other hand, multiplied wherever we moved.

As dusk fell over the operational staging area above Morobe on the night of 29 June 1943, a task force of infantry from the 41st Division loaded into all the available 532d barges; namely, 29 LCVPs and two captured Tap barges, and set out for a landing behind the Jap lines at Nassau Bay only a few miles below Salamaua. Never before in the southwest Pacific had the allies attempted a landing behind the Jap lines. These men were pioneers in amphibious warfare.

A and B Companies, 532 Amphibious Engineers and the 162 Infantry at Nassau Bay

Escorted by only three PT boats, the convoy inched northward a few miles off the enemy-held coast through the inky darkness and into ever increasing rain, wind and heavy seas. Natives who had lived in the vicinity for years said later that the storm on that particular night was the worst within their memory. There were supposed to be allied patrols on two small islands along the course to flash distinguishing lights so that the convoy could frequently check its course, but the storm made the location of these lights impossible.

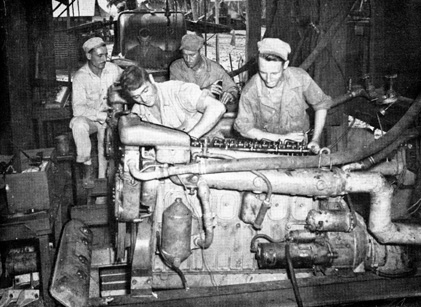

Oro Bay, New Guinea. Feb 1944. Rebuilding a boat motor in

the shop of 1570 Heavy Shop Co., 562 Engr Boat Maint Bn.

Front left: Tec 5 Neborsie D Perona,

Front right:

S/Sgt James B Connors, Jr, Mid Left: 2d Lt Joseph A Carreno,

Mid Right: T/Sgt John L Cathey, Extreme Rear: Tec 5 William T Chaplin.

The PT boats were too fast even at their lowest speed for the convoy and could not effectively guide it. Their craft cruised at twenty-five knots, ours at eight. One wave of boats got off the course entirely and went beyond the objective beach. Realizing they had lost the convoy they returned to Mageri Point, This proved most fortunate, for the boats of this wave were the only ones available for several days to run resupply missions to Nassau Bay.

The main group of boats finally located the landing beach. An Aussie patrol from the mountains had infiltrated through the Jap lines to the objective beach and flashed recognition signals to the convoy. They were barely visible in the murky, rainy darkness. The Japs had noticed the flashing signal lights and to create confusion also began to flash meaningless signals with the hope that the boats would land directly in front of their gun positions. But the Amphibs were not to be fooled for they directed their boats straight toward the lights of the Aussie patrol and pulled their throttles wide open. It was obvious to the experienced boatmen that the barges could not be beached successfully in the churning surf. which was now running twelve feet high, but orders were to land that night. So land they did, an hour after midnight, even though the boats were tossed about like match sticks as they approached the shore. Much equipment, weapons and ammunition were lost in the landing but every soldier was put safely ashore. Most of the boats were unable to retract and twenty-one of them were left swamped on the beach, twisted in every direction while the surf pounded them into distorted shapes within a few minutes. The boatmen salvaged what they could from the wreckage, including some machine guns taken from the boat mounts. They then reported to the infantry commander and were assigned a place in the perimeter for defense of the beachhead against the Jap attack they knew would come. The enemy was known to have considerable strength in the area but it was not until the next evening that the Japs struck. The delay was explained later when a captured Jap captain said the roar of the boat motors, as they sought to get off the beach, sounded to the Japs like tanks were being landed. They refrained from counter-attacking until they found out that the American forces were small and had no tanks.

As darkness fell over the creepy jungle on their second night ashore, the Amphips were well dug in along the beachhead’s southern perimeter. It was their job to defeat any Jap counterattack on that flank This task was a far cry from the operation of landing craft but one look at the broken LCVP hulls scattered along the beach behind them and their knowledge that about seven hundred Japs were two hundred yards in front of them decided what they had to do. Their situation was desperate for only part of the force landed and much of their ammunition and some of their weapons were lost in the raging surf. There was little hope for prompt reinforcements for all knew of the shortage of landing craft.

With no previous experience in the wily Jap infantry tactics the Amphibs did not know what to expect, but they had heard stories of the tricks the Japs had tried to pull on the Yanks, and so they alerted themselves for some sort of ambush. They had not long to wait, for on the first exchange of rifle fire, two figures loomed out of the jungle darkness ahead of them. The first figure was definitely that of a Jap with both hands stretched over his head, one of them still clutched his “Tommy gun.” It appeared that he was being marched along at the point of a rifle by a fellow American trooper; however, when both were in the midst of the Amphibs, the “captor” also proved to be a Jap and they began to blaze away incessantly at their surprised victims. Luckily, they were poor shots even at such close range and their plan was quickly thwarted. An M-1 bullet in the head dropped the first Jap and the sharp thrust of a hunting knife in the throat of the other quickly accounted for him. Toward morning the enemy, some of whom spoke a few words of perfect English, attempted to seduce the Amphibs from their hiding places and foxholes by slithering through the brush close to them and calling out: “All you engineers fall in, Hey, Joe, Come on out, you Yanks, your boats are coming in, and Come on out, we’re surrounded.” The Amphibs were wise and kept silent. Another of their treacherous tricks was to spray the immediate area with a submachine gun and then call out, “Is anybody hurt in there ?” If an answer were received, a second burst would be directed at once to the spot from which the voice seemed to come.

Before dawn a group of Japs suddenly made a Banzai charge. Although many were killed by our men, some managed to reach our foxholes. Hand to hand fighting ensued. Here our training at Ord on knives and judo paid dividends. At least a dozen Japs were disemboweled in these scraps and others failed to attack after hearing the screams of those gutted by American knives. It is no wonder that the Amphibs breathed a huge sigh of relief as the first streak of dawn broke over the eastern horizon. It was a costly night for the Japs, for their corpses were strewn in large numbers over the terrain, but the engineers did not escape unscathed. 2d Lieutenant Arthur C. Ely, Co A, 532d ESBR, of Scarsdale, New York, had led his men courageously during the first part of the fighting, but a chance sniper’s bullet killed him instantly while he was crawling to the aid of one of his wounded men. Throughout the remainder of the night six other men were killed and eight wounded. Caring for the dead and wounded the next morning was a grim aftermath to a fight for which every Amphibian can be proud. The brigade’s baptism of battle was over and victory had been achieved against overwhelming odds. The infantry commander later congratulated them on their splendid performance and disclosed to them that all would have been lost had not the boatmen made such a courageous stand and successfully held the south flank. He stated that all his reserves had been committed to repel a Jap attack from the north and not a man was available to help the hard pressed engineers on the southern flank.

Radio messages came back to the rear echelon at Morobe that there was urgent need on the new beachhead for medical supplies and ammunition, particularly hand grenades due to the fact that so much of these essentials had been lost in the swamped boats. On the second morning after the assault on Nassau Bay, 2d Lieutenant Charles C. Keele, Co A, 532d EBSR, of Dearborn, Michigan, set out from Morobe in a lone LCVP with a four-man boat crew to deliver a barge load of urgently needed supplies to the troops on the beleaguered beachhead. As they moved up the coast a jap plane sighted their barge and swooped down in a terrific strafing attack. Lieutenant Keele was seriously wounded and the boat badly damaged, but kept going. The crew begged him for authority to return so that they could get him to a hospital but he refused even to consider turning back. He knew how desperately the men at Nassau Bay needed his cargo. Disregarding his own weakened physical condition he directed emergency repairs to the damaged craft and ordered them to “get those supplies in if it is the last thing you do.” The men obeyed his command and the supplies were delivered to the waiting infantrymen. Shortly after Lieutenant Keele was brought back to the hospital, his life slowly ebbed away. For his courage and intense devotion to duty he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously. Later in Detroit his photo was displayed as a hero on a huge War Bond bill board.

The arrival of more troops on the beachhead during the next few days eased the situation and the Japs not already killed pulled back into the mountains or toward Salamaua. The Americans then started the drive on Salamaua. This consisted of step by step landings along the line as the steep mountains, wide streams, and thick jungle made movement through the interior almost impossible. Additional barges, manned by Amphibs, continued to bring in more troops, both American and Australian, artillery, tractors, jeeps, ammunition, rations, and many other essentials of an invading force. The weather having abated, the boats ran day and night with clock-like precision keeping the troops supplied from the sea as they moved on toward Salamaua. Returning boats evacuated wounded and carried mail, prisoners, and official dispatches back from the fighting front. They often landed reconnaissance patrols at night, silencing their motors and beaching almost under the very nose of Jap gun positions. At other times they would reconnoiter along the coast in broad daylight to draw enemy fire so the Allied artillery could locate and blast out the enemy emplacements. In addition to these jobs, special rescue missions were performed by the Amphibs. Several aviators who had had to bail out and parachute into the sea were rescued. The boats were proving themselves indispensable.

A few days after the landing on Nassau Bay two LCMs went to the rescue of the crew of a downed B-25 a short distance offshore, On the way they were strafed by four Jap Zeros that drilled nearly a hundred holes in the craft. Maintaining their determination never to turn back on a mission once begun, the crews, of the two boats continued on their course and rescued the crew of the rapidly sinking plane. The spirit of perseverance that the Amphibs displayed on this particular occasion is exemplary of their work throughout the entire Nassau Bay-Salamaua campaign and was to be repeated time and time again.

Officially the Nassau Bay operation was over. Off to a good start and with confidence in their ability to outwit the Japs, the Amphibs followed up this success by pushing on Salamaua and by launching two more rapid and decisive operations that were to give the allied forces possession of the vital supply bases at Lae and at Finschhafen.

|