Chapter VII

Hollandia and Tanahmerah

THE allied attacks from Buna to Saidor had forced a large number of the enemy to flee from the coast up into the hills where many of them were either killed by the natives or overcome by the ferocity of the jungle winds. Others though made the long overland trek and succeeded in rejoining the Jap forces along the northern New Guinea coast. Aerial photographs of the Wewak-Hansa Bay area revealed that it was being heavily fortified to resist the Aussies and Yanks who were driving northward from Saidor. Perhaps the japs planned to use Wewak as their “ace in the hole" and stake everything on its defense. If so, General MacArthur trumped their ace when he by-passed Wewak and opened a three-pronged amphibious offensive on Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea. This move was to isolate the Jap garrison at Wewak. During the next twelve months they were to make repeated attempts to break out of this trap but always unsuccessfully. It was not until the Spring of 1945, while the 2d ESB was busily engaged in mopping-up operations in the Philippine Islands, that Wewak fell into allied hands

The Hollandia operation was vastly different from the previous landings in which we had participated and for two reasons: it was much larger and the distance from the home base was far greater. The number of troops, landing craft, warships and carrier-borne planes involved in this operation exceeded anything we had ever hoped to see. The contrast with our first amphibious attack at Nassau Bay was astonishing. Undoubtedly the Japs were equally amazed and much less favorably impressed. The seven hundred-mile trip from Finschhafen to Hollandia was a longer hop for a combat mission than we had ever before attempted. Sufficient supplies and equipment to last for many days had to be taken in the first echelon for, once the beachhead was established, there could be no short dashes back to the main supply base for items that had been forgotten. Planning for such a gigantic operation had to be exact. Nothing could be overlooked.

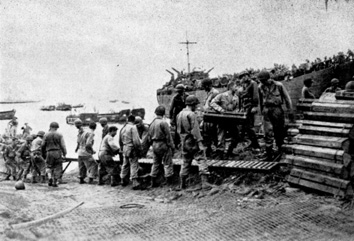

Tanahmerah Bay, Dutch New Guinea. 22 April 1944.

Shore Bn, 542 EBSR, operating beach and unloading

LSTs, LCMs, and LCVPs.

Another Special job of 2 ESB. Tec 5 William Graham,

Tec 5 Paul Dearing, Lt Col Garber and Tec 4 Clay Carter

of Co C, 542 EBSR placing buoys off Red Beach to

mark channels and under-water obstructions.

Shore Bn, 542 EBSR handling cargo on Red Beach.

Road of steel matting in foreground.

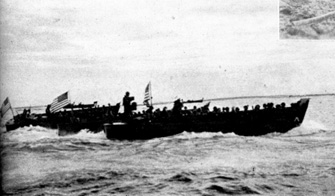

Boat wave formation of Co A, 542 EBSR carrying

assault infantry to Red Beach.

In this operation the 2d ESB was assigned the mission of supporting the two main divisional landing at Hollandia and Tanahmerah while the 3d ESB supported the landing of a regimental combat team at Aitape. Inasmuch as the 532d EBSR, located near Finscbhafen, had previously operated with the part of the 41st Infantry Division during the Nassau-Salamaua mission, General Heavey selected the 532d regiment to work again with that division in the landing at Hollandia. Friendships of Morobe and Nassau Bay were renewed. A full-scale rehearsal in preparation for the scheduled operation was held early in April. Strange to relate, it was held on the same Red Beach east of Lae where the 532d had landed Australian troops seven months before. Meanwhile, the 542d EBSR, most of which was located around Lae, was selected to work with the 24th Infantry Division in the assault of Tanahmerah. A rehearsal of that operation was desired by the commanders of both units, so the 542d moved from Lae to Goodenough Island where the rehearsal and staging for their part in the operation was to take place. The Amphibs were on Goodenough for such a short time that only a temporary camp was set up. The men of the Boat Battalion slept on the transports and naval craft that took them to Goodenough and that were also to carry them to the operational area on D-Day. On the day chosen for the "dry run," the 542d landed elements of the 24th Division at Taupeta Bay on the New Guinea mainland in a full-scale operation that employed the transports, LSDS, LSTs and their own barges. Both regimental rehearsals showed a few spots where better coordination was necessary and helped a great deal in getting the essential teamwork necessary for a successful amphibious operation.

The 2d ESB Support Battery, now under the command of Major Charles K. Lane, which by this time manned a force of 35 LVTS, or buffalos, in addition to its rocket and flak I.CMs had divided into two detachments, one to go to Hollandia and the other to Tanahmerah. The LVTS, although slow in speed, were used in making end runs and reconnaissance missions on D-Day. They later proved themselves most instrumental in the capture of the three Jap-held airstrips near Lake Sentani.

The 1000-mile jump from Goodenough and the 700-mile jump from Finschhafen were much too far to run the small brigade landing craft under their own power, so the Navy came to our rescue on this problem. It was agreed that the naval transports would leave their own landing craft on the near shore and carry our boats and crews in their stead. Davit space on the LSTs was furnished to carry the LCVPS. They also furnished us with three LSDS, which were in effect floating drydocks, to carry our LCMs loaded with tanks and bulldozers, those two very critical pieces of equipment necessary for a successful landing.

Let's compare the convoy of the Hollandia operation with that of the Nassau Bay mission only ten months earlier. For the Nassau Bay mission we had 30 landing craft, including two captured jap boats, and an escort of only two PT boats. For the Hollandia mission we had 280 landing craft, including buffalos, rocket and flak boats, LCMS, LCVPs and navigation control boats. Our escort consisted of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, rocket and personnel LCIS, subchasers, tugs, transport vessels and, for the first time in the southwest Pacific, escort carriers with their fighters and bombers ready to protect the convoy when it was beyond the reach of land-based planes. Is it any wonder that every American who participated in that operation felt within himself an inner glow of pride? The American Eagle was beginning to show its claws.

Off Manus Island in the Admiralties the two convoys, one from Goodenough and the other from Cape Cretin, united to form one immense convoy that seemed to stretch in all directions to the distant horizon. On 21 April they started out at first on a false course northward toward Palau to mislead any hidden coastal watchers, lurking jap planes or submarines that might try to plot the convoy's true objective. Then, after dusk, when the convoy was far away from the Admiralties, every ship suddenly wheeled to port and headed on a direct course toward Hollandia.

Just as the branches of a tree spread out in all directions from its trunk toward the sky so did the tentacles of this invasion convoy slither out in all directions toward the widely separated beaches in the objective area. The first split in the convoy came when the 3d ESB task group cut to port and disappeared over the horizon toward Aitape. Only a few miles offshore from the main Hollandia beachhead, another task group, the 542d, veered to starboard and sped toward Tanabmerah Bay. The main convoy carrying the 532d EBSR task group and the 41st Infantry Division continued on its course until it was only a few miles outside of Humboldt Bay. At the appointed hour every warsbip in the convoy opened a thunderous barrage on each of the four previously-selected landing beaches. Rockets swished. Planes from the carrier escorts bombed and strafed. The devastation ashore was terrific. Meanwhile, the small landing barges and buffaloes of the 532d Task Group, under the command of Colonel Alexander M. Neilson of Minneapolis, Minnesota, were being floated and loaded with passengers. Waves were organized and the dash to the beaches began. The initial waves met practically no opposition and the troops were landed safely. Buffaloes made subsidiary landings at Depapre and Pim since the rough coral reefs precluded the use of the landing barges on these beaches. Supported by the overwhelming fire of the rocket and flak LCMS, they likewise encountered no opposition. The landings on the two beaches of Tanahmerah Bay by the 542d were almost replicas of the Hollandia assaults. The bombardment was just as intense and the opposition as scant. As the infantry pushed inland they soon discovered the reason for this sudden absence of opposition. Once again the Japs who had survived the barrage had fled to the hills in panic. Food for their morning meal was found already cooked but still uneaten. Stores, weapons and personal equipment of every kind had been left behind in their mad scramble to vacate the area.

The amphibious part of the invasion clicked probably better than any previous operation in which we bad participated. Everything went as planned. However, the work on the shore was a different story for the landing craft poured troops and supplies ashore much faster than they could be removed. All beaches at Hollandia and Tanahmerah proved more difficult than aerial photos and intelligence had indicated. They were very shallow, backed up by a hinterland of almost impenetrable mangrove swamp, and with absolutely .no existing exits. At Tanahmerah a stream behind the main landing beach was identified from aerial photos as only "10 to 20 yards." It actually proved to be a swamp armpit deep extending inland from 100 to 400 yards. It is superfluous to say that the shore engineers had a big job cut out for them. No one had to put out a sign worded: "Danger, men at work," for there were no onlookers. Everyone was busy. Although the beaches were greatly over-congested and the terrain for dump areas was far from satisfactory, all Naval transports were unloaded on D-Day and got away before dark. There were no enemy air attacks that day. Planes bearing the star and bar insignia saw to that.

In the nights that followed, an occasional jap bomber managed to slip through our air cover and antiaircraft defense and drop his eggs before he was shot down. The planes never returned to their bases. but the damage was already done. The Emperor would be proud. To the Jap pilots nothing else mattered.

Early in the evening of their second night ashore a red alert was sounded in the 532d area on White Beach 1. The sound of a diving jap bomber sent the men rushing for their foxholes. Antiaircraft fire opened and tracers streaked toward the oncoming plane. The men waited. Down he came..... nearer . . . nearer., and then, with a sharp zoom upward, he was away. Hear 'em?..... Bombs! Get down! . . . Whoom! Vhoom! Whoom!-as rapid as that, and it was over.

Coming out of their foxholes the men were told that one of the bombs had landed harmlessly in the water, another on the sandy beach, but the third had obviously scored a direct hit on a huge jap gasoline dump. Flames rapidly spread to our adjoining supply area. Supplies, records, ammunition, rations--everything that was needed to carry on the attack-was in that gigantic stockpile. The rush to unload the ships and the lack of a wide dispersal area had forced us to pile the supplies in the only possible direction - upward. And now everything was in danger of complete destruction by fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Brockett soon had every man at work building a fire break in the supply dump. Gasoline drums were rolled to the right and left to cut a thirty-yard open strip from the beach through the area. Bulldozer operators were on the spot pushing barrels and supplies into the water. Human supply chains were organized and the supplies passed from one man to another until they reached the safety zone. Roller conveyors were hastily set up. Every man worked frantically to save everything he possibly could. Suddenly ammunition began to explode and the flames shot higher into the sky. The work put into the construction of the fire break was in vain for the flames jumped across it as if it was not even there. The men still did not stop but instead doubled their determined efforts. The fire continued to burn for several days with a resultant loss of around eight miIlion dollars worth of supplies. But it wasn't the money that mattered so much to those men on the newly-won beachhead, it was the loss of thousands of tons of badly needed supplies and equipment. Casualties were not heavy due to the prompt action of the boatmen, shore engineers and medical personnel who performed heroically that night.

Major (later Lt. Col.) Elmer P. Volgenau, who was a brigade observer aboard an LST waiting to land at White Beach, reported:

"The holocaust on White Beach as viewed from the sea was so awesome and terrifying as almost to defy description. Great billowing black clouds of smoke were flung thousands of feet into the air from exploding drums of gasoline, while the oil, lubricants, rations, vehicles, and hundreds of tons of miscellaneous stores and gear burned below it in a solid, hideous, frightening wall of flame five hundred feet in the air for a mile and a half along the beach. Through this dense pall of smoke and flame all kinds of ammunition set up a pyrotechnic display to end all boyhood impressions of Fourth of July fireworks. The spitting, vicious crackle of millions of rounds of small arms ammunition, grenades, and engineer explosives permeated with increasing waves of sound the shattering, crashing, crumbling roar and rumble of barrage after barrage of heavy artillery shells. In all directions, in all colors of the rainbow, rockets, signal flares, and white phosphorus shells sprayed out like all hell let loose. The fierce, eerie glare made faces look green in the half light. Shortly after the 2d ESB working and rescuing parties evacuated the beach due to the tremendous heat and danger of exploding projectiles of all kinds, the raging fire reached its maximum intensity in an intensity of destruction that made everyone gasp. None who saw it will ever forget the White Beach fire at Hollandia set off by one unlucky jap bomb. Among the "lessons learned the hard way by all ranks was 'Do not pile more supplies on a beach than the shore working parties can handle efficiently'."

In the midst of the action Ist Lt. (later Major) Wortham W. Dibble, Co. B, of Sumter, South Carolina, remembered that, just before the fire started, he had seen a wounded infantry soldier carried from the scene of the attack and placed in a dug-out about one hundred yards down the beach to await evacuation. The spreading fire and exploding ammunition caused everyone to flee from that area. Lt. Dibble had not seen the wounded infantryman, so he quickly called several of his men together and with great coolness he took them to the dug-out from which they moved the man to safety. Later examination showed the dug-out area to be scorched beyond recognition.

1st Lt. Robert L. Heath, Co. D, of Fort Meyer, Florida, saw to it that boats to evacuate casualties were signalled ashore and that the men were safely transported from the area. During the action he was injured but he refused medical treatment, preferring to "patch" himself up and continue with his work until every man was evacuated.

Another officer, 2d Lt. (later 1st Lt.) Robert F. Dalton, Hq. Co. Sh. Bn., of Mansfield, Ohio, ran to the assistance of six wounded men who were lying in the middle of the firebreak with gasoline fires raging not more than twenty-five feet on either side of them. He saw that these men were removed to a safe area and then dashed into the fire to rescue another helplessly wounded man who had taken refuge in what he believed to be a comparatively safe foxhole. That act of heroism undoubtedly saved the man's life for the next morning that foxhole was filled with debris and blackened dirt.

In a catastrophe of this sort the men wearing the Red Cross brassard are always in greatest demand. The annals of military history are full of accounts where the first aid men have somehow or other always been in the midst of things to bring comfort and medical treatment to casualties. Without them, war would be much more grim and the cost in human lives far greater. Fortunately, our medical amphibs were present on White Beach I that night.

Upon arrival at White Beach 1 on D-Day the Collecting Platoon of Company B, 262d Medical Battalion, had set up their aid station in the center of the dump area where they had easy access to the entire beachhead. When the fire started the next night Captain Vincent S. Cunningham, the Commanding Officer, of Arverne, New York, immediately alerted and directed the movements of his men. His instructions throughout the action were sharp and concise: "Get the litters . . . first aid kits . . . blankets . . . move out . . . teamwork counts . . . don't get excited clear those cots . . . bring him in lie quiet . . . boric acid . . . bandage adhesive . . . splints . . . tie that up. . .keep going . . . don't stop . . .." All that night and until noon the next day Captain Cunningham, 1st Lt. (later Capt.) Stephen A. Swisher III of Des Moines, Iowa, and their forty-four men worked feverishly. The litter bearers moved continuously through the holocaust of burning dumps and tremendous explosions. Again and again they returned to the inferno to rescue their comrades while the remainder of the personnel stayed in the aid station to treat the wounded. Many lives were saved by the effective care they so efficiently provided. It was only after all casualties and personnel had been evacuated from the danger area that the platoon retired to a place of safety.

The highest award that can be attained by any military organization, the Presidential Unit Citation, was bestowed upon this platoon on 22 September 1944. The last sentence of this citation to which nothing further need be added reads as follows:

"The heroism and determination of every man in this platoon, operating under the most hazardous and adverse conditions, exemplifies the highest traditions of the military service."

Meanwhile, the Support Battery buffaloes and flak boats were continuing their reconnaissance of the Hollandia area. On the morning of the initial assault two of their rocket LCMs and four LVTs carrying troops attacked and silenced the enemy on Hamadi Island just a short distance offshore from White Beach. Troops were landed on Pim jetty and, owing to the difficult terrain, the buffaloes continued to carry them some distance inland. That night the rocket and flak boats took up position across the entrance to jaufeta Bay to prevent the escape of enemy barges during the hours of darkness. Another section of the battery sank a 150-foot Jap tanker armed with a 3-inch gun and blew up two ammunition and two fuel dumps. The next day they reconnoitered Jaufeta Bay and found eighty-three jap barges and three 100-foot boats which were immediately confiscated. Some of them were repaired by our own boat maintenance personnel and put into use.

The infantry was then in a position to strike out for the three Jap airstrips north of Lake Sentani high in the hills and some fifteen miles from the beach. They fought their way along a narrow, boggy trail - the only pass to the airstrip-against stiff jap opposition. The Support Battery buffaloes were the only vehicles that could get over the rough terrain and it was up to them to keep the advancing infantry supplied. On the fourth day of the infantry advance they were stalled at the eastern tip of Lake Sentani. At this point the trail led along steep cliffs and the Japs had taken advantage of the terrain to blow out the bridges and throw up road blocks. Again the buffaloes provided the solution. Troops were loaded into them and, with rocket-equipped buffaloes forging ahead to blast the Jap lakeshore batteries, the Amphibs ferried them across Lake Sentani to a point near the airstrips, thereby flanking the Jap's forward defense line. The next day a similar end run was carried out. The Jap troops defending the ridge road were cut off and effectively bottled. The infantry closed in and mopped them up without much difficulty.

In an effort to prevent the buffaloes from landing, the Japs laid down a heavy barrage of mortar and antiaircraft fire but rockets from the Support Battery craft silenced these enemy batteries in a short time. One buffalo, however, was lost. It was a small price to pay for the advantage gained. The infantry went on to capture the airstrips during the next few days while the Amphibs continued to unload additional supplies for them on the new lakeshore beachheads. They also continued to run reconnaissance missions and to effect supplementary landing on several other beaches around the lake. Rocket buffaloes patrolled the shoreline and made repeated thrusts into the interior to blast out pockets of jap resistance.

Due to lack of space on the two beaches at Tanahmerah Bay for the storage of large stocks of supplies Colonel Benjamin C. Fowlkes, the 542d's Regimental Commander, of Santa Barbara, California, requested that the D-2 echelon previously scheduled to land in that area be routed to the Hollandia beachheads. The next few days were then spent in trying to fix up the Tanahmerah beaches, but progress was slow and work on the larger of the two beaches was soon discontinued in favor of building up the smaller beach at the bead of Depapre Bay. During the next ten days the regimental units were gradually moved to Hollandia leaving only one provisional battalion composed of Companies C and F at Tanahmerah.

While the Tanamerah beaches were being developed, the Support Battery craft attached to that task group conducted many scouting missions further up the coast as far as Matterer Bay. A rocket-equipped flak LCM under the command of 2d Lt. (later 1st Lt.) George W. P. Swenson of Flushing, New York, was out on one of these patrols one day when natives in canoes approached his craft. Lt. Swenson talked to them in Malay and Pidgin English and found they claimed to know the location of jap guns in nearby Demta Bay. Taking the two native leaders aboard as a precaution against treachery, they set out for the bay. As the boat moved into the harbor, its 37mm and 20mm guns opened up on the position pointed out by the natives. Coming into range, they let go some rockets. Japs were seen running up a path toward the mountains. The Amphibs mowed them down with machine guns. They closed in and strafed the thatched houses clustered together up the shore from which the Japs of the garrison continued to flee. They landed and a group of them ran ashore, armed with grenades, tommy guns, carbines, pistols and a bazooka. Sergeant William Smith of Watertown, Massachusetts, spotted and shot a Jap gunner as he tried to train a Lewis gun on the party. Lt. Swenson got two more with hand grenades. They found six gun positions which S/Sgt. Melvin S. Johnson of New Athens, Ohio, and M/Sgt. Vernon Ward of Moselle, Illinois, shelled with a bazooka. They captured a wounded jap who, when questioned, said the Jap garrison had numbered about 150. More dead were found but all the others had fled into the hills, One flak LCM manned by only one officer and eight men had routed 150 Japs singlehandedly. Lt. Swenson loaded his men and the prisoner aboard their barge and started back to Tanahmerah. On the way they met a convoy of landing barges and support craft from Company A, 542d, loaded with a battalion of infantry that was enroute to the same beach in Demta Bay whence he came. He related his experience to them and gave them information on the condition of the beaches and the estimated enemy strength. When the convoy reached the beach they shelled it again and the landing was affected with no opposition whatsoever. Lt. Swenson and his boat crew had done a good job in wiping out this opposition and for his display of leadership and gallantry in the face of enemy fire he was awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Tanahmerah Bay, Dutch New Guinea. 23 April 1944. General view

of Red Beach on D+1. 542 EBSR boats in foreground with

Engineers on beach.

Another small landing without opposition was made at the native village of Wari between Hollandia and Tanahmerah on the second of May. The village chief had informed the division headquarters that over one hundred Japs had gathered in his village and many of them were armed with machine guns. This news was received by the 542d early in the morning and at one o'clock that afternoon a force of landing barges from Company A under the command of 2d Lt. (later 1st Lt.) John B. Bryan, Jr., of Geneva, New York, and two Navy rocket LCIs were deployed across the beach in front of the village. Twenty minutes later the first wave landed without a shot being fired. The beach was not too good and many propellers were chewed up and the bottoms scraped on the sharp beach coral. The landing was successful from a tactical standpoint. It was soon learned that the Japs had been in that village the night before but at dawn had split up and left the village in opposite directions. Two infantry patrols were immediately sent out and several of the japs were captured in a nearby village. They were taken back to Tanahmerah in the 542d barges. In three subsequent missions to Wari the detachment evacuated a total of sixty-six prisoners.

That just about winds up the Hollandia-Tanahnierah Bav operation insofar as the actual fighting is concerned. The units began to develop their separate camp areas and set up their maintenance shops. However, many of the Japs who had fled into the hills during the initial phases of the invasion without food and equipment soon got hungry. About a month later they had reached the point of near-starvation, They tried to bargain with the natives or steal from them, but that source of food was limited. They knew that the Americans had large piles of rations and supplies on the beaches and calculated that it was worth the chance to try to infiltrate into the area and steal whatever they needed. It is quite possible that some may have gotten through successfully, but the alert perimeter guards spotted many of these infiltrators and killed them on sight. To relate each of these incidents would probably be quite boresome, but there are a few that can be quoted directly from the official reports:

"On 24 May 1944, lst Lt. Robert P. Molosso of Egg Harbor, New Jersey and seven enlisted men from Company B, 532d EBSR, contacted a party of six japs including one officer. The enemy fired two shots at Lt. Molosso's party and when ordered to surrender, refused to do so. All the Japs were killed."

"On the 31st of May one jap walked into the Boat Battalion area of the 532d and was killed by Company B men while attempting to escape."

"On 1 June PFC Frank Kosier, Hq. Co. Sh. Bn., 532d, of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, while on guard on the perimeter, fired on two Jap soldiers. The next morning fresh pools of blood, pieces of bandage, and a raincoat bearing the insignia of a Jap Major were found at the spot where the two Japs were last seen. A few days later a patrol found two dead japs only a short distance away, Fresh bandages were found on the wounds. Their deaths were credited to Pfc. Kosier."

"On 5 June, PFC. Dallas Hayes, Hq. Co. Sh. Bn., 532d, of Hornbeek, Tennessee, shot a Jap infiltrator through the hand but he escaped into the jungle. The next morning a patrol scouted the area and the wounded jap was found in a cave less than 25 yards from the perimeter. Upon being sighted the jap charged out of his hiding place in another escape. He was shot and killed by Sgt. John T. McConnell of Pocatello, Idaho, and Pfc. John R. Connolly of Leonardtown, Maryland."

"On 7 June the perimeter was alerted by a sound in the brush nearby. Pvt. Orlando A. Carpenella, Hq. Co. Sh. Bn., 532d, of Bronx, New York, moved closer to listen. At this time Pvt. George W. Connelly of the same company and of St. Paul, Minnesota, saw a jap charge Pvt. Carpenella. He killed the jap before any damage was done."

And so it goes. During the first twenty days of June the guards on the 532d perimeter at Hollandia shot and killed fourteen infiltrators. As late as the month of September the Japs continued to attempt these sneaky tactics, but always unsuccessfully. A few readily surrendered to the Amphib guards. So great was their hunger that their only choice was surrender or death and to some of them surrender was preferable to slow death or hari-kari.

The 562d Boat Maintenance Battalion established its boat yard and repair shops on Tieweri Point under the direction of Major Shotsman of Knoxville, Tennessee. As time went on and improvements were made, this became one of the "show" installations of Hollandia. Many Army and Navy officers visited it and commented favorably on the efficient shops established in a short time in the wilds of New Guinea.

With the Hollandia area under American control the forces of General MacArthur had taken a big step toward the reoccupation of the Philippine Islands. However, they were still hundreds of miles from their goal and the Jap-held Schouten Islands with their powerful land and air defenses presented a formidable barrier. We would first have to control those islands. , The next chapter relates the part the 2d ESB played in the capture of the islands ,of Wakde, Biak, and Noemfoor, all in the Schouten group.

Tanahmerah, Dutch New Guinea.

April 1944.

All of the comforts of home with none of the

responsiblities. Lt Col Garber, Tec 5

William Graham, Tec 5 Paul Dearing and

Tec 4 Clay Carter of Boat Bn, 542 EBSR,

aboard an LCVP, have fresh eggs

purchased from natives.

A company street 300 miles back from Japs.

Our Spare parts warehouse at Hollandia.

|